Why Economic Resilience Matters in a World of Crises

In today’s world, crises seem to come one after another – from global recessions and pandemics to social unrest, climate disasters, and geopolitical conflicts. These shocks don’t just occur in isolation; they often overlap and reinforce each other, causing widespread disruptions. Yet not all economies cope with crises in the same way. Some countries are able to contain the negative effects and bounce back quickly with minimal losses, while others take much longer to recover and may even suffer irreversible setbacks that permanently derail their development. In this context, the concept of economic resilience – essentially an economy’s ability to absorb, recover, and adapt in the face of shocks – has become a major priority for policymakers worldwide. A resilient economy can withstand crises with fewer damages, restore growth faster, and even emerge stronger, whereas a less resilient one might see prolonged recessions, social turmoil, or lasting damage to its productive capacity. For ordinary citizens, this isn’t just abstract economics: it means jobs, incomes, and stability are far better protected when the economy is resilient to shocks.

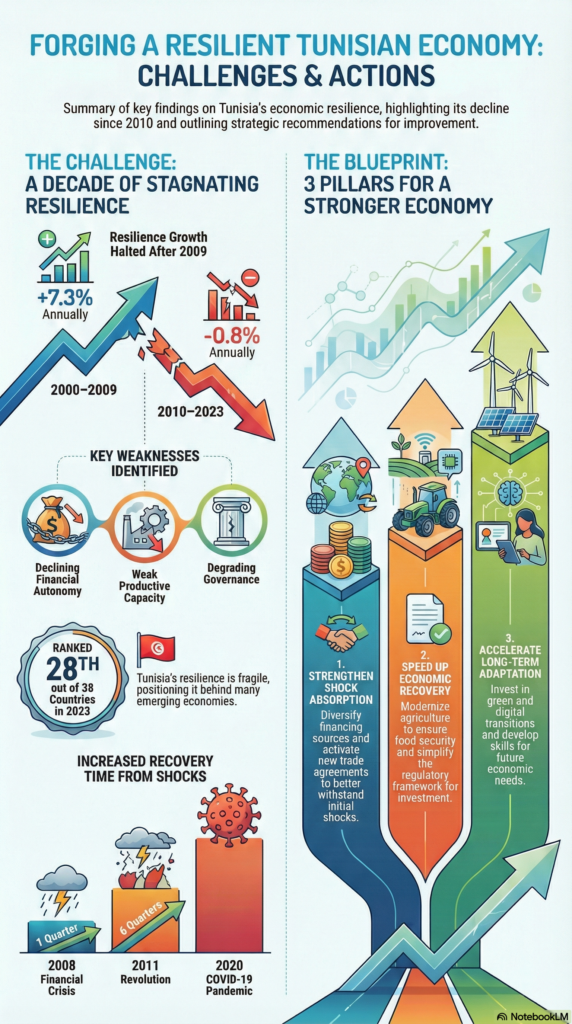

Tunisia is no exception to this urgent need for resilience. As a small open economy, the country has been repeatedly exposed to external and internal shocks over the years. These shocks have at times led to serious economic disruptions that spilled over into social and political instability. On the bright side, observers have noted that Tunisia has shown a certain degree of resilience in the face of crises – managing to weather storms despite over a decade of sluggish growth since 2010. The question now is: how resilient is Tunisia’s economy really, and what can be done to strengthen it further? A new policy report by the Tunisian Institute of Competitiveness and Quantitative Studies (ITCEQ) delves deeply into these questions, measuring Tunisia’s economic resilience and drawing lessons from both history and international comparisons. In this blog post, we break down the report’s key insights – in accessible terms – to understand why resilience matters and how Tunisia can build a stronger buffer against whatever crisis comes next.

Tunisia’s Trial by Shocks: A History of Crises Since 1980

Tunisia’s economy has experienced repeated shocks and upheavals over the past four decades. Since 1980, the country’s growth has swung through cycles of expansion and recession under the impact of various crises – some originating abroad, others stemming from domestic turmoil. Notably, Tunisia recorded three years of negative economic growth that mark severe breakdowns of its economic system. These three episodes correspond to pivotal crises in Tunisia’s modern history:

- 1986 – a financial and economic crisis on the eve of structural adjustment, which exposed an unsustainable fiscal situation and extreme external dependency.

- 2011 – the Revolution, which upended the country’s institutional foundations and ushered in a period of prolonged instability.

- 2020 – the COVID-19 pandemic, which paralyzed productive sectors and exacerbated social vulnerabilities.

Each of these shocks hit the economy hard, but Tunisia’s ability to rebound has varied greatly over time. Before 2011, Tunisia often managed to recover from shocks quite quickly and with limited damage. For example, after external shocks like the 2001 global downturn (post-9/11) or the 2008 financial crisis, Tunisia’s economy saw only a modest dip (losses well under 1% of GDP) and recovered within one quarter to its previous growth path. This implies that in earlier decades the economic system had buffers that allowed a quick bounce-back – whether it was fiscal space, external support, or flexible adjustment mechanisms.

However, since 2011 Tunisia’s resilience appears to have weakened. The 2011 revolution itself caused a sharp ~4% quarterly GDP contraction and it took about 6 quarters (1½ years) for GDP to return to its pre-crisis level. Even more strikingly, the COVID-19 shock in 2020 led to an unprecedented 18.5% drop in quarterly GDP, and the economy took 19 quarters – nearly 5 years – to climb back to the 2019 GDP level. In other words, Tunisia did eventually recover from COVID-19, but at a very slow pace compared to earlier crises (previous shocks typically saw a rebound in just one quarter). Such a drawn-out recovery illustrates how vulnerabilities had built up: the pandemic’s effects lingered through the economy, and the usual engines of rebound (like fiscal stimulus or external demand) were insufficient to restore growth quickly. The prolonged slump after 2020 translated into lost jobs, income setbacks for households, and a delay in returning to “normal” life for many Tunisians. This contrast – quick recoveries before 2011 vs. halting recoveries after – suggests that Tunisia’s economic resilience was stronger in the past and has eroded in the face of recent challenges.

What explains this decline in resilience? Part of the answer lies in the cumulative structural stresses on Tunisia’s economy. The ITCEQ report notes that many shocks have impacted the same vulnerable sectors again and again: for instance, repeated droughts hit agriculture (threatening food security), terror attacks and global downturns hit tourism, and depleting oil/gas reserves hit energy production. These sectoral weaknesses, combined with external dependence (relying heavily on imported food, energy, and external finance), have limited the economy’s capacity to absorb and bounce back from shocks. In essence, Tunisia’s buffers have been worn thin over time. This underscores why actively strengthening resilience is so important – so that the next crisis doesn’t knock the economy off course for years, with all the social pain that entails.

Measuring Resilience: The ISRE Index and How It Works

To get a comprehensive picture of Tunisia’s economic resilience, the ITCEQ report develops a Synthetic Index of Economic Resilience for Tunisia, abbreviated as ISRE. This index is built on a rigorous conceptual framework that draws from economic literature and Tunisia’s specific context. The idea is to capture, in one quantitative tool, the many factors that determine how well an economy can withstand and recover from shocks. In constructing the index, the researchers consider two complementary approaches to resilience: one by dimensions and another by capacities. Let’s break down what that means in simple terms.

1. Resilience by Dimensions: The ISRE<sup>d</sup> (dimensional index) looks at the structural pillars of the economy that contribute to resilience. The report identifies four key dimensions and aggregates various indicators under each:

- Economic and Financial Autonomy: How economically independent is Tunisia? This covers things like the diversity of trade and investment partners, debt levels, foreign reserve buffers, and financial system stability. Essentially, it gauges whether the country has the economic freedom and stability to maneuver during a crisis (e.g. not being overly at the mercy of foreign capital or imported essentials).

- Productive Capacity: How strong and dynamic is the domestic productive base? This includes the vitality of businesses (especially small and medium enterprises), industrial diversification, technological adaptation, and the skill level of the workforce. A more robust and flexible production system can adjust under stress (firms can pivot to new markets or products, workers can up-skill, etc.), which aids resilience.

- Social Cohesion: How well does the social fabric hold together in tough times? This dimension looks at social stability, the presence of safety nets, inequality levels, and the general sense of societal trust and inclusion. Social cohesion is crucial because a united society can better absorb shocks without descending into unrest, and communities can support each other during recovery.

- Governance: How effective are institutions and public services? This captures government effectiveness, the quality of institutions, policy credibility, and crisis management capacity in the public sector. Good governance can proactively mitigate shocks (through prudent policies) and respond efficiently when crisis hits, thereby reducing damage.

By compiling data for a wide range of indicators under each of these four dimensions, the ISRE<sup>d</sup> gives an overall resilience score. Think of it as taking the economy’s vital signs across those four areas – autonomy, production, social cohesion, and governance – to see how well the fundamentals can support resilience. A higher score means stronger fundamentals. In Tunisia’s case, these dimensions highlight where the country’s strengths and weaknesses lie structurally (more on that later).

2. Resilience by Capacities: The second approach, ISRE<sup>c</sup> (capacity index), organizes resilience around the time-frame of response to shocks. This aligns with the three stages we touched on earlier – absorption, recovery, and adaptation – which correspond to short, medium, and long-term aspects of resilience. An economy is deemed resilient if it can perform in all three of these capacities:

- Absorption capacity is the ability to withstand the initial impact of a shock without a systemic breakdown. In practical terms, when a crisis hits (say a sudden drop in tourism or a spike in import prices), can the economy absorb it in the short term? This could mean having buffers like reserve funds, flexible budgets, or emergency plans that prevent the shock from causing a collapse. High absorption means the economy can take a punch without severe immediate damage – like a shock absorber in a car smoothing out a bump.

- Recovery capacity is the ability to quickly restore lost functions and return to normal growth in the medium term. This is about bounce-back: how fast can Tunisia replace what was lost and get back on its feet? It involves factors like how rapidly businesses can reopen or rehire, how soon consumer demand picks up, and what policies are in place to jump-start the economy post-crisis. Strong recovery capacity means a crisis might knock the economy down, but it doesn’t stay down for long.

- Adaptation capacity is the ability to learn from the shock and make longer-term changes so that the economy not only recovers but transforms to become more resilient and efficient. Adaptation is about structural change and innovation: using the crisis as an impetus to fix underlying issues, diversify industries, adopt new technologies, or improve institutions. This is a longer-term, forward-looking capacity. If absorption was about surviving the hit, and recovery about getting back up, adaptation is about evolving – making sure that after the crisis, the economy isn’t just back to where it was, but is better prepared for the future.

The ISRE<sup>c</sup> index aggregates various indicators that correspond to each of these capacities (for example, fiscal space and import cover for absorption, speed of investment rebound for recovery, R&D and education metrics for adaptation, etc.). Tunisia’s overall resilience can then be judged by how it scores on each capacity and in combination.

By constructing these two indices (by dimension and by capacity), the ITCEQ report provides a holistic measurement of economic resilience. This allows us to track resilience over time and also compare Tunisia with other countries on a like-for-like basis. It’s like giving Tunisia’s economy a resilience “rating” from multiple angles. Importantly, such a measure isn’t just academic – it identifies concrete weak points (say, if the adaptation capacity is low, or governance dimension is lagging) so that policymakers know where to focus their efforts to shore up resilience.

Progress and Setbacks: Tunisia’s Resilience Trends from 2000 to 2023

One of the most illuminating parts of the ITCEQ analysis is looking at how Tunisia’s resilience index has evolved over time – essentially a timeline from 2000 up to 2023. This two-decade span covers a lot of real-world events (global booms and busts, Tunisia’s own revolution, regional upheavals, pandemics, etc.), allowing us to see whether the country’s underlying resilience has been strengthening or weakening in response. The results tell a story of mixed progress: some areas have improved, while others have deteriorated, leading to a resilience that is still fragile and in need of bolstering.

On the positive side, Tunisia’s overall resilience index (ISRE) has shown a mild upward trend on average. Between 2000 and 2023, the composite resilience score edged up from about 0.4 to 0.5 (on a 0 to 1 scale), an average increase of roughly 0.9% per year. This suggests that despite all the turmoil, Tunisia’s economy in 2023 is slightly more resilient than it was in 2000. However, that aggregate improvement hides a crucial detail: the gains came almost entirely from one area – the adaptation capacity. In fact, the adaptation sub-index grew by about 3% annually, reflecting efforts (and perhaps necessity) to change and innovate structurally over the years. By contrast, the other two capacities actually declined: the shock absorption and recovery capacities both weakened by about 0.6–0.8% per year on average. In short, Tunisia became better at long-term adaptation, but worse at withstanding immediate shocks and quickly bouncing back.

Why would adaptation improve while absorption and recovery worsen? The report’s interpretation is insightful: Tunisia’s pattern of response to repeated crises has been to rely increasingly on slow-moving, structural adjustments (adaptation) because the quick-response mechanisms have faltered. For example, when faced with shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic or recurrent droughts, the country did not have ample short-term buffers (fiscal or otherwise) to cushion the blow immediately, nor strong momentum to rebound swiftly. Instead, what recovery eventually happened was driven by longer-term changes – businesses and workers slowly adjusting to new realities, or the economy finding new equilibrium over years. This is evident in agriculture: repeated droughts forced adaptation such as shifts in crops and reliance on imports, since the ability to absorb the shock (through irrigation infrastructure or grain reserves) was limited and recovery to prior production levels was sluggish. In essence, Tunisia’s resilience has become more of a slow burn – the economy does adjust and survive, but through a painful, drawn-out adaptive process rather than a swift rebound. While adaptation is certainly better than not adjusting at all, the weakening of absorption and recovery is problematic because it means more immediate damage from crises and more protracted hardships for the population in the interim.

We can see this dynamic in the data trends. The shock absorption capacity of Tunisia peaked around 2009 and then declined steadily in the 2010s, with an especially sharp drop after 2018. By recent years, the absorption index value had fallen significantly, indicating that the economy’s short-term shock absorbers (like financial cushions, flexible policies, etc.) had “worn out” post-2011. Similarly, the recovery capacity index, which had been on an expansion path in the 2000s, entered a downward phase after 2010, deteriorating at an annual rate of about -3.5% after 2009. This decline aligns with what we observed in actual events: slow and difficult recoveries from the 2011 and 2020 shocks. The report notes that the mechanisms that previously allowed Tunisia to restore equilibrium quickly in the short-to-medium term have run out of steam in the post-revolution period. Contributing factors likely include strained public finances (little room for stimulus), policy uncertainty, and structural bottlenecks that prevented a quick restart of growth.

Meanwhile, adaptation capacity initially showed an impressive rise in the 2000s – improving by about 9% per year from 2000 to 2009 – but then stagnated in the 2010s, even slipping slightly (around -0.4% per year from 2010 to 2023). Tunisia had built some potential for adaptation through investments in human capital (education, etc.) and early steps toward innovation, but after 2011 progress slowed. For instance, gains in educational attainment and technology adoption plateaued, and brain drain accelerated as many skilled Tunisians sought opportunities abroad. This means that even the adaptation capacity – which was the main driver of resilience gains – is not living up to its full potential. The report warns that if human capital and innovation efforts falter, Tunisia’s capacity to structurally transform in response to shocks could be compromised. In other words, adaptation has been the “engine of change” for Tunisia’s resilience, especially in coping with challenges like climate change (water scarcity) and shifting global markets. But that engine needs to be fueled continuously by training, innovation, and investment; otherwise, it will lose momentum.

There is one clear bright spot in Tunisia’s resilience story: Social cohesion has held up relatively well and even strengthened in certain respects. According to the report’s findings, the Social Cohesion dimension of the resilience index improved over time, which has been a crucial saving grace. Essentially, Tunisian society has maintained a degree of stability and solidarity that helped cushion the blows from economic shocks. For example, despite economic stagnation, Tunisia avoided large-scale social breakdown; community networks, remittances from abroad, and social programs (though strained) helped many families get by during crises. The report describes social cohesion as an “absorber” of shocks that limited the impact of other vulnerabilities. Because the social fabric remained relatively intact, it prevented economic hardships from spiraling into complete chaos. This aligns with the observed fact that, even when GDP was hard-hit (like in 2020), Tunisia did not descend into widespread unrest to the extent some other countries might have under similar strain. A preserved social fabric – trust in communities, a tradition of mutual aid, and some baseline social safety nets – provided resilience at the grassroots level. This is encouraging, because it suggests that investing in social cohesion (education, health, social protection, inclusive policies) not only benefits people day-to-day but also pays dividends when crisis strikes by making society more resilient. Indeed, the report notes that Tunisia’s social dimension gradually consolidated over the years, reflecting a capacity among the populace to absorb shocks and support adaptive efforts.

In summary, the 2000–2023 timeline for Tunisia shows resilience that is fragile and unbalanced. The country has managed to keep its head above water through turbulent times, mainly thanks to long-term adaptive adjustments and a strong social backbone. But the erosion of immediate shock absorbers and rapid recovery mechanisms is a worrying trend. It means Tunisia is more vulnerable to getting knocked down hard by crises and staying down longer. The challenge ahead is to reinvigorate those short- and medium-term capacities (absorption and recovery) while continuing to bolster long-term adaptation. The next section looks at how Tunisia stacks up against other countries – which will further highlight where Tunisia is lagging and where it’s doing comparatively well.

Tunisia’s Resilience in International Perspective

Resilience, of course, is relative – countries facing the same global shock can have very different outcomes. The ITCEQ report doesn’t just measure Tunisia in isolation; it compares Tunisia’s resilience index to a broad sample of other countries for the most recent year (2023). This comparative analysis is crucial for understanding where Tunisia stands: Is Tunisia one of the more resilient emerging economies, or does it lag behind? And what specific weaknesses are dragging it down relative to its peers? The findings show that Tunisia, unfortunately, is falling into the lower tiers of resilience globally, especially when looking at the capacity to recover and adapt.

Using the dimension-based resilience index (ISRE<sup>d</sup>), Tunisia in 2023 ranks 28th out of the countries assessed, putting it in the category of **“intermediate-to-low resilience” economies. This means that on the structural pillars (economic autonomy, production capacity, etc.), Tunisia is not among the worst performers, but it’s certainly not among the strong performers either – it sits in a lower-middle position. Interestingly, the report notes that Tunisia’s overall profile is comparable to several emerging economies like Turkey, the Philippines, or Brazil, rather than to its immediate North African neighbors. In other words, Tunisia’s resilience challenges are similar to those of some mid-tier emerging markets, rather than, say, mirroring the resilience of Morocco right next door (which actually scores a bit better). This 28th place ranking underlines that Tunisia’s resilience is fragile, weighed down by economic and institutional vulnerabilities. The weak points are mostly in the economic and governance dimensions, where Tunisia scores relatively low (for example, Economic & Financial Autonomy and Governance both have modest scores around 0.42, ranking 30th+ among peers). These low scores reflect Tunisia’s high external dependencies, fiscal strains, and governance issues in recent years. By contrast, Tunisia’s Social Cohesion dimension stands out more positively, with a score of ~0.62 and a rank of 19th. That confirms what we observed in the trend: social cohesion is a relative strength for Tunisia, helping to offset some of the weaknesses in the economic and institutional domains. Still, even with a decent social score, Tunisia’s composite structural resilience remains in the lower-middle pack globally – it has a lot of catching up to do to reach the resilience levels of more robust emerging economies.

The picture becomes starker when looking at the capacity-based resilience index (ISRE<sup>c</sup>). By this measure, Tunisia ranks 32nd in 2023, which places it firmly among the “low resilience” countries in the sample. The drop from 28th to 32nd ranking when shifting from dimensions to capacities indicates that Tunisia’s performance is even worse when judged by how it can absorb/recover/adapt, as opposed to the broad structural factors. Essentially, Tunisia’s real-time response capacities to shocks are lagging behind most other countries, even some that have similar structural profiles. The report notes that Tunisia sits among the least resilient group, though it still manages to outperform the majority of Sub-Saharan African countries (except South Africa) and a couple of fellow Arab countries like Egypt and Algeria. So, in a global context, Tunisia is ahead of some of the weakest performers, but it’s well behind many of the emerging economies it would like to emulate. Tellingly, Morocco and Argentina, which are in the same broad “low resilience” category, managed to secure somewhat better positions than Tunisia in the ranking. This is a wake-up call: countries with comparable challenges have taken steps that gave them an edge in resilience, meaning Tunisia could likely do the same with the right policies.

Drilling down into the details, we see which capacities are dragging Tunisia’s rank down. The adaptation capacity emerges as the weakest link by far – Tunisia ranks 34th on adaptation, near the very bottom of the list. This is a critical finding: it implies that Tunisia has very limited room for structural adjustment and innovation compared to other countries. Even though Tunisia’s adaptation index improved slightly over time, it wasn’t enough to keep pace internationally. Many peers have been rapidly advancing in areas like technology adoption, education, and economic diversification, whereas Tunisia’s progress has been slower. The result is that Tunisia is falling behind in its ability to transform and modernize in response to new challenges. The report underscores that despite some gradual improvements, Tunisia’s performance on adaptation remains below international standards, highlighting an urgent need for boosting things like innovation capacity, human capital development, and climate change preparedness.

The recovery capacity is also quite low – Tunisia ranks 31st, confirming that its ability to rebound quickly from shocks is subpar. This aligns with the observed regression in the recovery index over the past decade. Compared to other countries, Tunisia struggles to restore economic balance swiftly after a crisis, which could be due to factors like cumbersome business climates, limited fiscal stimulus capability, or slow project implementation. The modest ranking in recovery illustrates that Tunisia often takes longer to get back on track after a downturn, whereas more resilient countries manage to reignite growth sooner. This lag in recovery means Tunisia endures a more prolonged dip in jobs and incomes post-crisis, which can have lasting social repercussions.

On a somewhat better note, Tunisia’s absorption capacity is relatively higher – it ranks 26th, better than its other capacities. This suggests that in the very short term, Tunisia can mitigate the initial impact of some shocks a bit more effectively than it can recover or adapt. A rank of 26th is still only middle-of-the-pack, but it indicates, for instance, that Tunisia’s immediate crisis response mechanisms (like short-term fiscal measures, central bank actions, or emergency reserves) are not as deficient as its longer-term adjustment mechanisms. The absorption capacity gave Tunisia a “relatively more favorable position compared to the other capacities” – meaning Tunisia can sometimes cushion the first blow of a crisis (for example, the government did enact emergency support during COVID-19 that softened the initial economic free-fall). However, even this absorption performance is moderate by international standards. Tunisia’s rank 26 out of ~35 countries is nothing to brag about; it simply indicates that Tunisia has a bit more short-run resilience than some peers, but is far from best-in-class.

In summary, the international comparison paints a sobering picture. Tunisia’s economic resilience is not competitive right now – globally, it is in the lower ranks, especially when it comes to recovering from shocks and adapting to new realities. Its strengths (like social cohesion and some shock absorption ability) are outweighed by significant weaknesses (particularly innovation/adaptation and speedy recovery). The fact that Tunisia lags behind even countries with similar development profiles shows that there is room for improvement through better policies and reforms. It also highlights that Tunisia must focus on its weakest links – adaptation and recovery – which the report identifies as priority levers to boost overall resilience. The next section turns to exactly that: what actionable steps can Tunisia take to shore up its resilience and climb into a higher league of resilient economies?

Building a More Resilient Tunisia: Key Recommendations

After diagnosing the state of Tunisia’s economic resilience, the ITCEQ report doesn’t stop there – it offers a blueprint of policy recommendations to strengthen Tunisia’s ability to withstand and bounce back from crises. Crucially, the report suggests that these reforms be structured around the same three capacities of absorption, recovery, and adaptation. By targeting each stage of resilience, Tunisia can build a comprehensive defense system against shocks: first absorbing the impact without collapse, then recovering quickly, and finally adapting and transforming to reduce vulnerability to future shocks. Below, we summarize the key recommended actions in each category, translated into accessible language, to show how Tunisia can move “from fragile to resilient.”

- Absorption (Short-Term Shock Cushioning): To reinforce the economy’s shock absorbers, the report emphasizes improving financial buffers and maintaining stability in the immediate face of crisis. This includes reducing costs and broadening financing sources for businesses – and making it easier for them to access credit – so that companies have more liquidity and flexibility to weather short-term hits. When firms can get affordable loans or have lower overhead costs, they are less likely to go under during a downturn, which saves jobs and production. Another key measure is to diversify Tunisia’s trade partnerships and activate existing trade agreements to broaden export markets. The goal is commercial autonomy: if one market falters (or one supply route closes), having multiple trading partners ensures the economy can pivot rather than absorb the full shock. This has become very apparent with events like the Ukraine war – over-reliance on certain import sources (say for wheat or energy) can be devastating, so Tunisia needs plan B and C markets. Additionally, investing heavily in economic and social infrastructure is highlighted as a win-win for resilience. Expanding public investment (including via public-private partnerships) in areas like healthcare, education, social safety nets, transportation, and logistics will not only create jobs now, but also improve the country’s collective services and connectivity, which helps maintain stability during crises. For example, a stronger healthcare system can manage a pandemic better (absorbing that shock), and robust logistics networks keep food and supplies flowing even under stress. Such infrastructure also fosters social cohesion – when people have access to good services even in hard times, society remains calmer and more united, which itself boosts absorption and adaptation capacity. In short, Tunisia should fortify its immediate defenses: more financial breathing room for economic actors, more diversified trade links, and stronger public infrastructure and safety nets to protect people when shocks hit.

- Recovery (Restoring Balance Quickly After a Crisis): To speed up the rebound phase after a shock, the report suggests several targeted interventions. One is to stabilize key productive sectors, especially agriculture, through modernization and climate resilience measures. Agriculture is singled out because it’s both vulnerable to shocks (like droughts) and critical for food security. Policies could include improving water management (so droughts do less damage), providing financial support or insurance to farmers for climate-related losses, and modernizing farming techniques for efficiency. The idea is that if agriculture can be made more resilient, Tunisia won’t face severe food shortages or price spikes after events like droughts or import disruptions – allowing the economy to recover faster and with less social pain. Another recommendation is to simplify administrative procedures and stabilize the regulatory framework for businesses (especially the tax and investment rules). This is crucial because one thing that slows recovery is uncertainty and red tape. If entrepreneurs and investors are unsure about rules or bogged down in bureaucracy, they will hesitate to re-invest and hire after a crisis. By cutting needless red tape and ensuring policies (like taxes) are predictable, Tunisia can encourage quicker business resurgence and attract investment even in the aftermath of shocks. For instance, a company recovering from a crisis might be more willing to reopen or expand if they know the tax regime won’t suddenly change adversely next year. Lastly, the report urges establishing a clear institutional mechanism for crisis management and risk monitoring. This means setting up a coordinated system (possibly a dedicated unit or task force) that takes charge when crises strike – clarifying who is responsible for what, ensuring rapid decision-making, and monitoring emerging risks in real time. An example could be a national emergency economic council that includes government, central bank, and regional authorities, ready to deploy a response plan (financial aid, regulatory adjustments, etc.) as soon as an external shock is detected. The recommendation also highlights strengthening local capacities for crisis management – in other words, empowering municipalities and regions with “rapid response units” to implement relief and recovery efforts on the ground. The faster and more organized the response at all levels, the faster the recovery. Think of it like a fire drill: Tunisia needs a practiced protocol for economic shocks so that everyone knows their role and the recovery process can kick in immediately, not months down the line. By modernizing agriculture, streamlining business regulations, and institutionalizing crisis-response, Tunisia can significantly trim the time it takes to recover from future shocks, reducing economic losses and hardship duration.

- Adaptation (Long-Term Transformation and Resilience-Building): This is arguably the most forward-looking and transformative set of recommendations, aiming to ensure Tunisia doesn’t just survive crises, but comes out stronger through structural change. A central theme here is investing in people and skills for the future economy. The report calls for strengthening mechanisms to retrain and reorient workers from declining sectors to growing ones, and to promote professional mobility towards high-potential industries. For example, if certain industries (say some traditional manufacturing or public sector jobs) are stagnating, Tunisia should have programs to re-skill those workers in areas like digital technology, renewable energy, or other “futures” sectors so that human resources are not wasted. Coupled with that, there’s an emphasis on developing “future-proof” skills – digital skills, green tech competencies, and modern managerial know-how – aligned with the emerging needs of the labor market. Tunisia has a well-educated youth population, but to adapt, their education and training must match what a changing global economy demands. Initiatives might include updating curricula, vocational training in IT and renewable energy, and partnerships with tech firms for skill development. Moreover, talent retention is critical: the report suggests creating an environment that encourages skilled Tunisian professionals to stay (or return) by offering continuous training, attractive career opportunities, and better working conditions. Tunisia has suffered a “brain drain” of engineers, doctors, and IT professionals – plugging that leak by valuing talent is vital for building adaptive capacity, since it’s these skilled individuals who drive innovation and change.

In terms of technological and economic transformation, the recommendations are bold. Tunisia should accelerate its digital transformation and green transition as a strategic move to reduce external dependencies and leapfrog into new industries. This means fast-tracking projects like e-government, digital infrastructure, and renewable energy expansion. By doing so, Tunisia can become less dependent on imported fossil fuels or outdated technologies and more self-reliant. For instance, investing in solar and wind energy not only creates jobs and reduces carbon emissions, but also curbs the vulnerability to oil price shocks (a clear adaptive win). The report specifically notes that embracing digitalization and ecological transition is an adaptation strategy “to reduce commercial, energy and technological dependence”. Alongside this, the mobilization of “green finance” is recommended – basically, tapping into global funds available for sustainable projects, and channeling investment into local green industries and clean technologies. By developing local green supply chains and clean tech adoption, Tunisia can carve out new growth sectors and export opportunities (imagine Tunisia becoming a hub for solar technology in Africa, for example). The concept of a circular economy also features in the advice: Tunisia should promote circular practices (recycling, efficient resource use) to optimize resource usage and ensure more self-sufficiency in supply chains while preserving strategic resources like water and energy. This would make Tunisia less vulnerable to commodity swings and import disruptions, and also protect vital resources (water scarcity is a real threat) thereby improving long-term sustainability.

Finally, the report urges a revival of industrial and innovation policy with resilience in mind. This involves supporting high value-added sectors and stimulating innovation among small and medium enterprises (SMEs), as well as encouraging diversification in products and markets. In practical terms, Tunisia could identify a few strategic sectors (say, agro-tech, pharmaceutical, aerospace components, ICT services) and actively promote them through incentives, R&D support, and infrastructure, so that the economy isn’t overly dependent on a narrow base (like low-end manufacturing or a single export market). Likewise, helping SMEs innovate and scale up would build a more agile domestic industry that can adapt to changes. The report even suggests integrating resilience as a priority in national and sectoral development strategies – meaning every major economic plan should consider how to enhance shock-resistance and adaptability. It’s about adopting a resilience mindset at all levels of planning. By transforming its workforce skills, accelerating digital and green innovations, and refocusing on high-value, diversified production, Tunisia can move toward what the report calls a “systemic and transformative resilience”. This would position Tunisia not just to survive crises, but to thrive in spite of them, turning each challenge into an opportunity to upgrade the economy.

In summary, the policy roadmap for a more resilient Tunisia is clear: build stronger buffers for the short term, enable faster recovery in the medium term, and drive continuous adaptation and innovation for the long term. These reforms, spanning financial measures, structural projects, and governance improvements, are all within Tunisia’s reach. They do require political will, efficient execution, and often, upfront investments. But the payoff could be enormous – a Tunisian economy that can protect the livelihoods of its people when the next crisis hits, and quickly rebound and reinvent itself in a virtuous cycle.

Conclusion

Tunisians have learned through hard experience that economic resilience is not a luxury – it’s a necessity in today’s unpredictable world. Building resilience means that when the next global downturn or unforeseen crisis arrives, jobs won’t vanish overnight, prices won’t skyrocket uncontrollably, and the nation won’t be knocked off its development path for years. The ITCEQ report gives a comprehensive, and at times sobering, assessment: Tunisia’s economy has shown admirable grit in adapting to shocks, but it has also absorbed a lot of punishment that better resilience could have prevented. The good news is that resilience is not a fixed trait; it’s something that can be strengthened through wise policies and collective effort. By shoring up its economic foundations, improving crisis response systems, and investing in the ingenuity of its people, Tunisia can move from merely coping with crises to thriving despite them. That means a more secure future for every Tunisian – where a bad year doesn’t erase a decade of progress, and where opportunities outlast storms. In a world of compounded crises, resilience is the promise that tomorrow can still be better than today, and it’s a promise within Tunisia’s power to keep by taking the bold actions outlined above. The time to act is now, before the next shock hits – because resilience, once built, is the gift that keeps on giving.

Sources:

- ITCEQ (2025). Résilience de l’économie tunisienne : Mesure et Positionnement extérieur – Policy Brief. Tunis: Institut Tunisien de la Compétitivité et des Études Quantitatives (analysis of Tunisia’s economic resilience, historical shocks, and international comparison).

- INS & ITCEQ data (2020–2023). GDP impact and recovery durations for Tunisia’s major shocks (showing the economic losses from 2011 revolution, COVID-19, etc., and the time taken to recover pre-crisis GDP levels).

- ITCEQ (2025). Policy Brief on Economic Resilience – Key findings on resilience indices and recommendations (detailing the ISRE index construction, Tunisia’s capacity and dimension rankings, and proposed policy measures for absorption, recovery, adaptation).