LLMs Demystified: Pre-Training, Fine-Tuning, and Human Feedback Explained

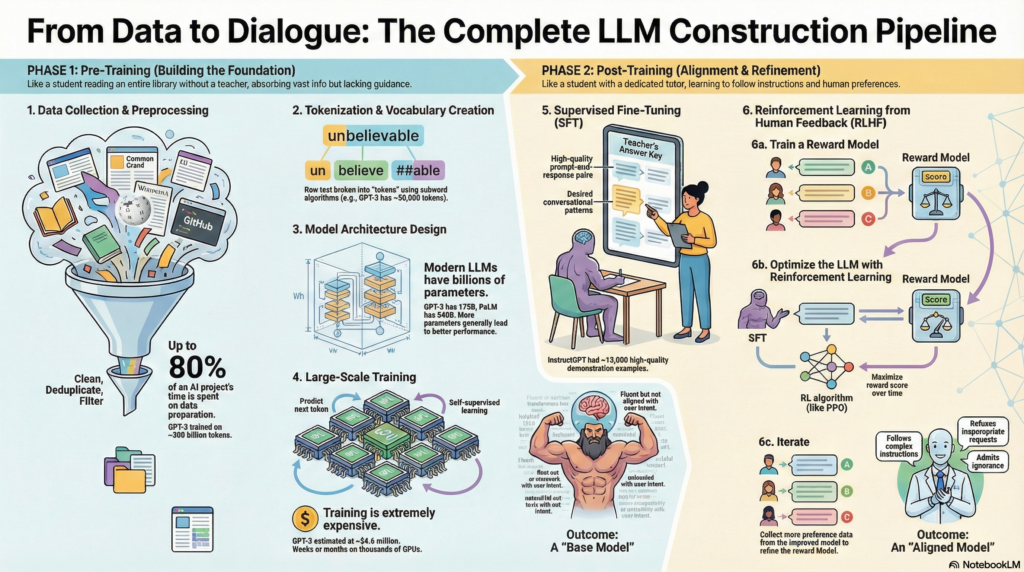

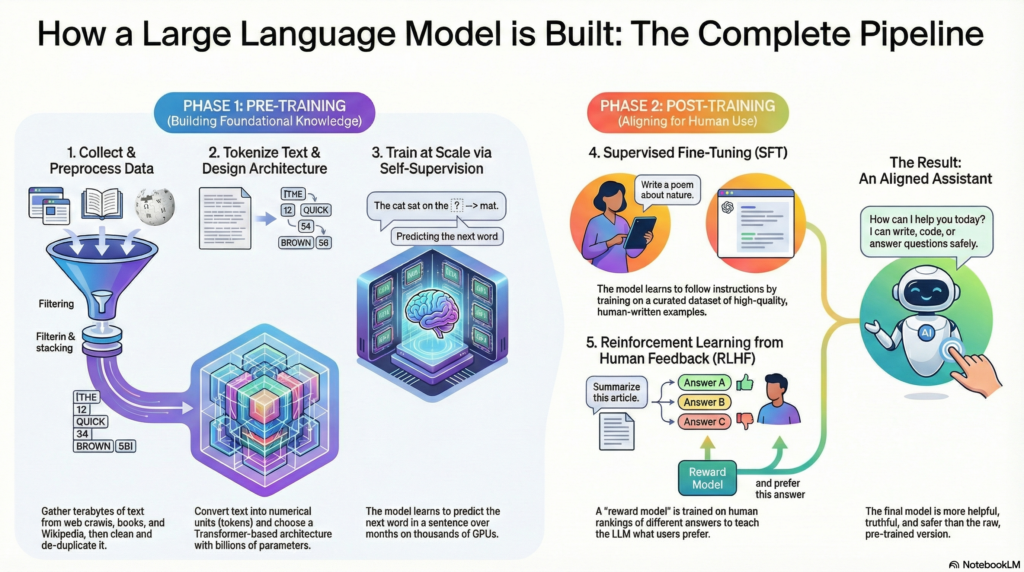

Developing a Large Language Model (LLM) is a complex, multi-stage process. At a high level, it involves an initial pre-training phase (where the model learns general language patterns from massive datasets) and a subsequent post-training or alignment phase (where the model is fine-tuned and taught to follow desired behaviors). An easy way to imagine this is to think of the LLM as a student: in pre-training, the student reads vast amounts of text (like learning from an entire library of textbooks without a teacher), and in post-training, the student receives guided instruction and feedback (like a tutor refining the student’s knowledge and manners). Below, we break down each stage in detail, covering key techniques, real-world examples, and challenges at every step.

Pre-Training: Building the Foundation

Pre-training is about laying a strong foundation for the LLM’s knowledge and language understanding. It consists of four major steps: (1) data collection and preprocessing, (2) tokenization and vocabulary creation, (3) model architecture design, and (4) large-scale training with self-supervised learning. In this phase, the model essentially teaches itself by predicting or filling in text, akin to a student doing self-study with a mountain of books. We’ll examine each step:

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The first step in creating an LLM is gathering a vast corpus of text data and preparing it for training. The quality, diversity, and size of this dataset are critical – they determine what the model can potentially learn. In practice, modern LLMs are trained on hundreds of gigabytes to terabytes of text, drawn from many sources to cover the breadth of human knowledge[1]. Common data sources include:

- Web crawls: Massive dumps of internet text (e.g. Common Crawl or OpenWebText) provide informal and formal writing across many domains[1]. For example, the GPT-3 model was trained on a filtered subset of Common Crawl comprising roughly 180 billion tokens of text[2].

- Books and literature: Large collections of e-books and digitized literature contribute well-edited, long-form text (e.g. BookCorpus or Project Gutenberg)[3]. These help the model learn coherent long-range structure.

- Encyclopedias and knowledge bases: Datasets like Wikipedia provide high-quality factual text[3]. Many models include the full text of Wikipedia (GPT-3 used ~10 billion tokens from Wikipedia[2]).

- Scientific and technical sources: Research papers, technical documents, or code repositories (like GitHub data) can be included to give domain-specific knowledge[3]. For instance, Meta’s Galactica model intentionally focused on scientific papers and textbooks to excel at scientific knowledge[4].

- Dialogue and social media: Datasets of conversations (e.g. forum posts, chat logs) or Q&A pairs help models learn interactive and conversational patterns[3].

Gathering such a broad dataset ensures the LLM isn’t narrow in scope – diversity improves the model’s cross-domain knowledge and generalization[5]. However, raw data from the web is noisy and unstructured. This is where preprocessing comes in. Data preprocessing involves cleaning and filtering the collected text to maximize signal and minimize garbage. Key preprocessing steps include:

- Removing unwanted content: Stripping out HTML tags, boilerplate website text, or other markup so that the model isn’t confused by irrelevant tokens[6].

- Deduplication: Eliminating duplicate or highly repetitive text segments. Redundant data can cause the model to overweight those examples or even simply memorize them. Removing near-duplicates helps prevent overfitting and data leakage (where the model’s test evaluations might inadvertently contain training data)[7].

- Quality filtering: Excluding low-quality or nonsensical texts. This can be done through heuristics or trained classifiers[4][8]. For example, one might filter out pages with too much profanity or random character sequences, or use a classifier to keep data similar to a high-quality reference (like Wikipedia)[9][10].

- Formatting and normalization: Converting text to a consistent casing, handling special characters or emojis (e.g. converting “👍” to the word “thumbs up”), and standardizing whitespace and punctuation[6][11]. Consistent formatting prevents the model from seeing two versions of the same thing as different.

- Redacting sensitive data: Removing personal identifiable information or privacy-sensitive content if it’s present, to avoid the model memorizing and regurgitating such details[12].

All these preprocessing steps aim to strike a balance between cleaning the data and preserving the richness of natural language. It’s worth noting that not all teams agree on how aggressively to clean data – for instance, some argue that keeping “the good, the bad, and the ugly” of language (typos, biases, toxic speech) is necessary so that the model learns to handle or avoid them, rather than pretending they don’t exist[8]. In practice, most large-scale efforts do perform substantial filtering to avoid obvious garbage and hate speech, but subtle biases in data are harder to eliminate completely.

Analogy: Data collection for an LLM is like collecting a gigantic library for a student. We want the library to cover as many topics and styles as possible (from science textbooks and classic novels to casual forum conversations) so the student gets a well-rounded education[1]. Preprocessing then is like curating and cleaning those books – removing any pages that are illegible or harmful, and highlighting quality material – so that the student isn’t misled by bad information. A famous real-world example is GPT-3’s dataset, which spanned about 300 billion tokens from sources like Common Crawl, books, Wikipedia, and news articles[2]. Even with careful curation, data quality remains a challenge: studies have found issues like overlapping test data and persistent biases in these massive corpora[7]. Data quality issues directly translate into model issues (hence the saying “garbage in, garbage out”[13]). Large teams today spend a huge amount of effort on data – by some estimates, up to 80% of an AI project’s time is spent on data preparation rather than model development[14][15].

Key challenges in data collection: Ensuring you have enough data and the right kind of data is non-trivial. For top-tier LLMs, the scale is so large that there’s concern we might “run out” of high-quality text on the public internet in the near future[16]. In fact, recent models already consume trillions of tokens (for perspective, 1 trillion tokens is roughly equivalent to the text in 15 million books!)[17]. Additionally, web data reflects human biases and can contain toxicity; filtering it sufficiently without removing important information is an ongoing area of research and debate. There are also legal and ethical considerations (copyrighted material, privacy of scraped content, etc.) when collecting large-scale data – issues that many organizations are grappling with as they build LLMs.

2. Tokenization and Vocabulary Creation

Raw text (characters and words) cannot be fed directly into a neural network. The model first needs the text to be converted into a sequence of discrete tokens, each represented by a numeric ID. Tokenization is the process of splitting text into these units and constructing a vocabulary of all tokens the model knows. Think of this as creating the model’s “alphabet” or “lexicon” – it defines how the model reads text and breaks it down for processing[18][19].

A naive tokenization approach might be to split on whitespace so each word is a token (e.g., “unbelievable” is one token). But this can lead to an impractically large vocabulary (hundreds of thousands of unique words, including inflections and misspellings) and problems with rare words (e.g., what about a misspelled word the model never saw?). Instead, modern LLMs use subword tokenization algorithms that strike a balance: words are broken into smaller pieces (subwords) such that the vocabulary is manageable yet we rarely encounter truly unknown tokens. Popular methods include Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), WordPiece, and SentencePiece, all of which build a vocabulary by starting from characters and merging frequently co-occurring sequences into bigger tokens[20][21]. For example, BPE might break “unbelievable” into [“un”, “believe”, “##able”] as three tokens (where “##able” indicates a suffix), if those subwords are common across the corpus. The final vocabulary might be on the order of tens of thousands of tokens for a large model – GPT-3, for instance, used a vocabulary of about 50,000 tokens, including basic byte-level characters to handle any text[22][23].

Crucially, each token corresponds to an integer ID, and the model ultimately works with sequences of those IDs[19]. This is why tokenization is needed: neural networks can’t directly ingest text, but they can deal with numbers. Think of tokenization as turning a sentence into LEGO pieces – each piece is a token that in isolation might not mean the whole thing, but together they can form the complex structures of language[24]. For example, the sentence “Nebius is the best” could be tokenized into [“Nebius”, ” is”, ” the”, ” best”] and then mapped to IDs like [5001, 40, 78, 312] (IDs are arbitrary here)[23]. The model sees the sequence [5001, 40, 78, 312] and treats it as numbers to process.

Designing the tokenizer involves deciding on the vocab size and algorithm. Larger vocabularies mean longer lists of possible next tokens for the model to choose from (making the prediction problem “easier” in terms of fewer steps, since common words can be one token), but also more memory usage and slightly more difficulty handling truly unseen words. Smaller vocabularies (e.g., character-level models) drastically increase sequence length (since a word might be 5-10 characters = tokens) and training difficulty, but they can theoretically represent any string without unknown tokens. Most LLMs find a sweet spot using subword tokenization so that common words stay intact while rare or complex words are broken down. This way, even if the model encounters a new word like a rare scientific term, it can fall back to piecewise understanding via subword tokens (e.g., a new protein name might be tokenized into meaningful chunks or letters that the model can still reason about).

Analogy: Tokenization is like teaching the student how to read by spelling out words. Instead of seeing a completely new word as an undefined concept, the student learns to break it into familiar syllables or letters. For an LLM, these syllables are subword tokens. By constructing a vocabulary of tokens, we’re giving the model the set of building blocks it can use to understand and generate text. If the pre-training data is the library of knowledge, the tokenizer is the language’s alphabet and phonics system for our AI student.

Key challenges in tokenization: There are trade-offs in this step. One challenge is out-of-vocabulary (OOV) handling – ensuring the tokenizer can encode any input text, including typos or code or emoji. Byte-level tokenization (as used by GPT-2 and GPT-3) helps here, because it can fall back to individual bytes for unknown sequences, thus no input is truly unencodable[22]. Another challenge is that the chosen tokenization can bias the model: for example, if the vocabulary merges certain words, the model might treat them as a single concept. Also, tokenization can affect performance on languages with different scripts or on multi-lingual corpora (where one might need a very large vocab or multiple tokenizers). These are typically resolved by careful vocabulary construction (possibly using multilingual SentencePiece for multiple languages, for instance). Overall, tokenization is often a one-time upfront design choice made before training begins – but it’s a critical one, as it defines the interface between raw text and the model’s numerical world.

3. Model Architecture Design

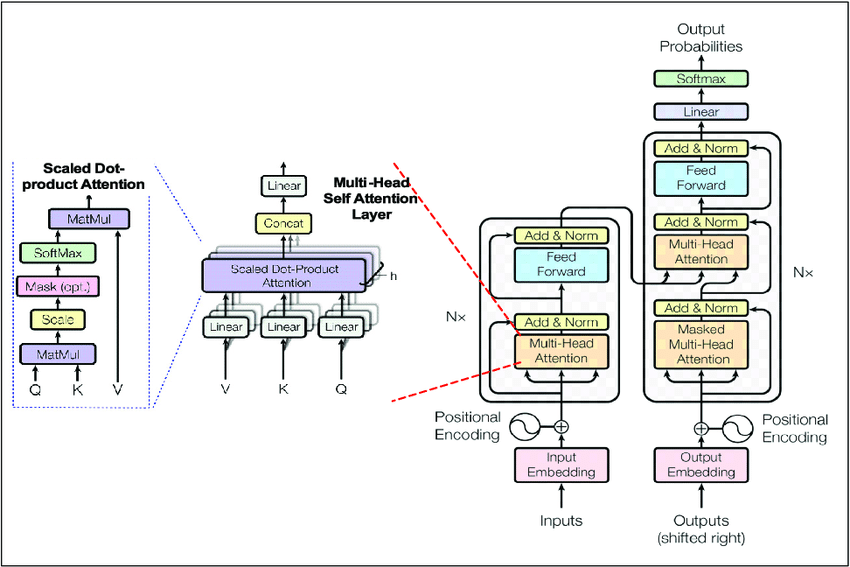

With data in hand and a tokenizer ready, the next consideration is designing the neural network architecture that will learn from this data. Modern LLMs nearly all use some variant of the Transformer architecture[25], which has become the de facto standard thanks to its powerful self-attention mechanism that enables capturing long-range dependencies in text. In a Transformer, the fundamental building block is an attention layer that allows the model to weigh the relevance of every other word in the sequence when processing a given word. These attention layers are interwoven with feed-forward neural networks and organized into stacked blocks (plus add-norm residual connections)[25]. By stacking dozens or hundreds of these layers, Transformers can build very sophisticated representations of language.

Figure: The Transformer model architecture, which is the backbone of most LLMs[25]. Each block (shown in the encoder-decoder diagram above) contains multi-headed self-attention and feed-forward sublayers with skip connections. Variants include using only the decoder stack (as in GPT-style models) or only an encoder (as in BERT). The Transformer’s ability to attend to context over long sequences is crucial for learning language structure.

Designing an LLM’s architecture involves decisions such as: How many layers (depth) should the network have? How wide should each layer be (the dimensionality of representations)? How many attention heads in the multi-head attention? What about special components like positional embeddings (to give a sense of word order), or feed-forward hidden size, or activation functions? These choices determine the model’s capacity and capabilities. Generally, larger models (with more layers and parameters) yield better performance, as shown by scaling studies[26]. For example, OpenAI’s GPT-3 has 96 layers and 175 billion parameters, an order of magnitude jump from its predecessor GPT-2 (which had 1.5 billion)[27]. Google’s PaLM model pushed this further to 540 billion parameters, and other research has explored even trillion-parameter scales. However, bigger isn’t always straightforwardly better – the returns can diminish, and the computational cost grows enormously.

In practice, teams often start from a known successful architecture and adjust it, rather than inventing something entirely new for each project. For instance, the EleutherAI team built GPT-NeoX-20B by taking the general GPT-3 architecture and making a few tweaks (using rotary positional embeddings, some parallelization in layers, etc.)[28]. Meta’s OPT-175B likewise aimed to replicate GPT-3’s architecture closely, with small changes in training hyperparameters and data scaling[29]. Reusing architecture patterns is helpful because it de-risks the training – if you use the same architecture as GPT-3, you can be more confident you’ll get a working model of similar quality (provided you have similar data and compute). Researchers also consider encoder vs. decoder designs: GPT-series models are decoder-only (they predict the next token based on previous tokens), BERT is encoder-only (it looks at the whole masked sentence bidirectionally), and sequence-to-sequence models like T5 or GPT-4 can use encoder-decoder stacks. Decoder-only models are most common for general LLMs that generate text, whereas encoder-only are common for understanding tasks. The architecture choice is tied to the pre-training objective (next-word prediction vs. masked fill-in, more on that next).

Analogy: If pre-training data is the textbook and tokenization is the language, then the model architecture is like the student’s brain or the blueprint of a learning machine. A Transformer with many layers and heads is akin to a brain with many interconnected neurons and regions specialized for pattern recognition. Designing the architecture is like deciding how complex and powerful of a brain your student will have – more neurons (parameters) and layers allow for more complex reasoning, but also require more “energy” (compute) and time to train. Just as human brains evolved with certain structures to process language, we design the LLM’s network structure (usually a Transformer) to be well-suited for language tasks.

Key challenges in architecture design: One major challenge is finding the right scale – you want a model big enough to capture the patterns in your data, but not so big that it becomes infeasible to train or deploy. There are empirical scaling laws that guide how performance improves with model size, data size, and compute, showing roughly power-law relationships[26]. These laws can inform whether it’s more efficient to invest in a bigger model or more data, for example. Another challenge is ensuring trainability: some architectures might be theoretically powerful but hard to train (prone to instabilities or not supported by existing frameworks). The Transformer architecture is a well-proven workhorse at this point, but training extremely deep Transformers still poses issues like vanishing gradients or convergence instability if not done carefully[30]. Researchers mitigate these with techniques like proper weight initialization, learning rate schedules, and sometimes innovative layer designs. Finally, memory limitation is a practical concern: a huge model might not fit on available hardware. Techniques like model parallelism, sharding, and recent innovations (sparse models, mixture-of-experts) all come into play to manage very large architectures. Designing an LLM architecture is thus about balancing ambition with practicality.

4. Training at Scale with Self-Supervised Learning

Once the data, tokenizer, and model architecture are ready, the next step is the actual training of the model – adjusting its internal weights so that it learns to predict text effectively. Pre-training of LLMs is typically done with a self-supervised learning objective, meaning the model learns from the data without any explicit human-provided labels. The most common objective is next-token prediction: the model reads a sequence of tokens and tries to predict the next token that should follow[31][32]. For example, if the sequence is “The cat sat on the”, the model might predict “mat” as the next token[32]. Another popular objective (used in models like BERT) is masked language modeling, where the model sees a sentence with some tokens hidden (e.g., “The cat sat on the [MASK]”) and must fill in the blank[31][33]. Both are self-supervised tasks because the “correct answer” is derived from the text itself (we know what word actually comes next or fills the blank from the original corpus). There’s no need for an external label – the data serves as its own supervision.

Training an LLM with these objectives is a massive undertaking. The training loop is conceptually simple: feed the model batches of token sequences, have it predict the next token for each, compute the error (difference between predicted and actual next token), and adjust the weights via backpropagation to reduce that error. Do this billions of times. In practice, doing this at the scale of an LLM requires distributed training on specialized hardware. State-of-the-art models are trained on clusters of GPUs or TPUs for weeks or months. For example, GPT-3 (175B parameters) was famously estimated to cost on the order of $4-5 million in compute and took several thousand GPU-days to train[34][35]. One way OpenAI achieved this was by using 1,024 GPUs in parallel, finishing the training in just over a month (where a single GPU might have taken centuries)[36]. Such parallelism is non-trivial: models are split across many devices (model parallelism), and data is pipelined in batches across them (data parallelism), coordinated with high-speed interconnects. Libraries like Megatron-LM and DeepSpeed have been developed to handle these large-scale training tasks efficiently[37].

Self-supervised training is like the mass practice of our student: the model reads each sentence and tries to guess the next word, over and over, across a vast corpus. Initially, it’s like a student guessing randomly. But gradually, by seeing where it was wrong and adjusting, the model starts to pick up on the statistical patterns of language – common word sequences, grammar rules, facts that often appear together, etc. After training over, say, 300 billion tokens, the model has essentially absorbed a huge amount of linguistic and factual knowledge in its weights. For instance, it will have seen many examples of how sentences are formed, how topics correlate with certain words, and even some reasoning patterns hidden in text. The result of pre-training is a general-purpose language model that can generate or continue text in a way that sounds remarkably human-like and knowledgeable (at least on topics present in training data). This is exactly what we saw with base models like GPT-3: without any further tuning, it could already produce essays, answer questions, translate, etc., by leveraging the general patterns it learned – though not always reliably or on-target, as we’ll address soon.

However, training at this scale comes with serious challenges:

- Computational cost: As mentioned, LLM training is extremely expensive. OpenAI’s GPT-3 incurred an estimated ${\sim}$4.6 million in compute[34]. Newer models like GPT-4 reportedly used orders of magnitude more compute (tens of millions of dollars worth)[38]. Only organizations with significant resources (or clever efficiency tricks) can undertake this. There is active research into more efficient training, such as using mixed-precision arithmetic, optimizer sharding, and even techniques to approximate or reuse computation. One interesting note is from MosaicML (now part of Databricks), which demonstrated you might train a GPT-3-level model for under $500k with the right optimizations[39], but that’s still a hefty sum. Compute cost also implies environmental cost (energy usage) which has raised concerns about the sustainability of blindly scaling up.

- Training stability: Training very deep networks can sometimes become unstable – the loss might explode (diverge) or get stuck. With billions of parameters, even a small glitch can blow up. Practitioners employ strategies like learning rate warm-up and decay schedules, gradient clipping, and careful weight initialization to maintain stability[30][40]. It’s common to monitor training closely; if divergence (a sudden spike in loss) occurs, one might have to restart from a earlier checkpoint with tweaked hyperparameters (e.g., a lower learning rate)[30][41]. As a best practice, teams often start training on a smaller model (maybe 1% of the full size) to validate the setup, then scale up, as some issues only appear at scale[42].

- Hardware failures and engineering: Running a training job on hundreds or thousands of GPUs for weeks is also an engineering feat. Hardware can fail; nodes can drop out. Systems need to be tolerant to interruptions, and saving checkpoints regularly is crucial[43]. Frameworks must synchronize gradients across GPUs, which is non-trivial at this scale. A lot of engineering effort goes into simply keeping the whole training pipeline running to completion.

- Overfitting and generalization: Surprisingly, the bigger the dataset, the less overfitting is a concern (models are often underfit even after seeing hundreds of billions of words). But still, ensuring the model doesn’t just memorize common sequences but actually generalizes patterns is important. Techniques like regularization or even intentionally leaving some data untrained for validation help to check that the model is learning meaningfully. Evaluation on held-out sets or standard benchmarks throughout training can indicate if the model is still improving or if it’s saturating.

- Emergent behaviors: An intriguing aspect of large LLMs is that they sometimes exhibit emergent abilities (sudden leaps in capability at certain scales) which are not present in smaller models[44]. These can be positive (e.g. better reasoning or few-shot learning) but also can include unexpected behaviors. This makes testing and evaluation during training important – to know what you’re creating, since it might be capable of tasks you didn’t explicitly train for.

In summary, by the end of the pre-training phase, we have an LLM that is very knowledgeable but also somewhat raw. It knows a lot about language and facts (learned from its “reading”), but it was trained purely to predict text, not to follow instructions or adhere to any goals. This leads to the well-known issues: a pre-trained LLM might generate plausible text that’s completely incorrect or inappropriate because its goal was never “tell the truth” or “be helpful” – it was just “complete the sentence in a statistically likely way”[31][45]. As a result, pre-trained models like the original GPT-3, while impressive, often misaligned with user needs – they might ramble off-topic, refuse to answer straightforwardly, or exhibit biases from training data[46][47]. This is where post-training comes in: we need to fine-tune and align the model to behave in desirable ways.

Post-Training: Fine-Tuning and Alignment

After pre-training, the model has general linguistic capabilities, analogous to a student who has read every book but hasn’t been guided on which answers or behaviors are preferred. The next stages involve aligning the model with human intent and specific tasks. There are two major post-training stages commonly used today: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) and Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). Continuing our analogy, SFT is like a period of classroom instruction or tutoring – the model is shown examples of good behavior and learns to imitate them. RLHF is like interactive feedback and coaching – the model’s outputs are reviewed by humans and it is coached to improve via a reward system, akin to giving the student critiques and gold stars to reinforce good answers. Let’s break down each:

5. Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT)

Supervised fine-tuning involves taking the pre-trained model and further training it on a smaller, targeted dataset of high-quality input-output examples. These examples are often handcrafted or curated to illustrate the tasks or behaviors we want from the model. In the context of building something like ChatGPT, the fine-tuning data might consist of prompts (questions or instructions) and ideal responses written by human experts. By fine-tuning on this, the model learns to produce responses that are more helpful, correct, and aligned with user expectations than the raw pre-trained model’s outputs.

For example, OpenAI’s InstructGPT work (which led to ChatGPT) gathered around 12,000 to 15,000 prompt-response pairs written by human labelers[48]. These prompts ranged from simple questions to complex instructions, and labelers wrote what they considered a good answer for each. The pre-trained model was then fine-tuned (via supervised learning) to mimic these demonstration answers[48]. In essence, the model is “learning by example” – it adjusts its weights so that given a certain instruction, it will produce an answer more like the ones the humans gave in the training set.

This stage can be seen as behavior cloning[49]: we have demonstrations of desired behavior, and we train the model to clone that behavior. The result of SFT is a model that we can call the aligned model (initial) or the SFT model. It typically is much better at following instructions or providing helpful answers than the base model. However, because the fine-tuning dataset is relatively small (thousands of examples versus billions of words in pre-training), the SFT model can still be imperfect and not generalize to every situation. It might learn to give safer or more straightforward responses on average, but it can still produce errors, omissions, or revert to pre-training behavior in unfamiliar scenarios[50]. Moreover, supervised fine-tuning has an inherent limitation: it requires lots of human effort to create the training examples, and scaling that up is expensive and slow[50]. It’s noted that OpenAI’s labelers spent a great deal of time to create those 12k examples, and producing, say, 10x more examples would be costly.

Analogy: SFT is like training the model with a teacher’s answer key. After the self-study phase, our student (the LLM) now sits down with a tutor who says: “When asked this question, here’s how you should answer.” By mimicking the tutor’s examples, the student picks up better habits. For instance, if the pre-trained model sometimes responded to a prompt with incoherent rambling, the fine-tuning data will show it a well-structured answer instead, and the model will learn to prefer that. It’s a supervised learning scenario, so it’s like a student doing homework assignments and being corrected by the teacher with the right answers.

In practical LLM development, supervised fine-tuning is often the first step toward alignment. Many organizations publish instruction-tuned versions of base models. For example, Meta’s LLaMA 2 model has a fine-tuned variant (LLaMA 2-Chat) that was trained on a blend of conversational data. Similarly, the open-source community took a base LLaMA and fine-tuned it on instruction-following data (like the Stanford Alpaca project). Even smaller examples exist, like Databricks’ Dolly model which was fine-tuned on a few thousand prompt-response pairs. All these are applications of SFT.

Key challenges in SFT: The main bottleneck is data quality and breadth. Because the fine-tuning dataset is manually curated, it must be high-quality. If the demonstrations have inconsistencies or biases, the model will learn those. Also, if they cover only certain styles or domains, the model might become overly specialized. There’s a known tension: fine-tuning can in some cases make the model lose some of its breadth or creativity, a phenomenon sometimes called alignment tax, where aligning to instructions causes a small regression in other capabilities[44][51]. Choosing the right prompts and ensuring a wide coverage of tasks can mitigate this. Another challenge is avoiding overfitting: with such a small dataset (relative to pre-training), it’s easy for the model to memorize the answers. Techniques like early stopping, regularization, or mixing some pre-training data back in can help keep the model general. Finally, SFT alone cannot fix all issues – the model might still output problematic content not seen in fine-tuning examples, or it might simply be limited in what it can do. This leads to the next stage, RLHF, which addresses those gaps by directly learning from human preferences.

6. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

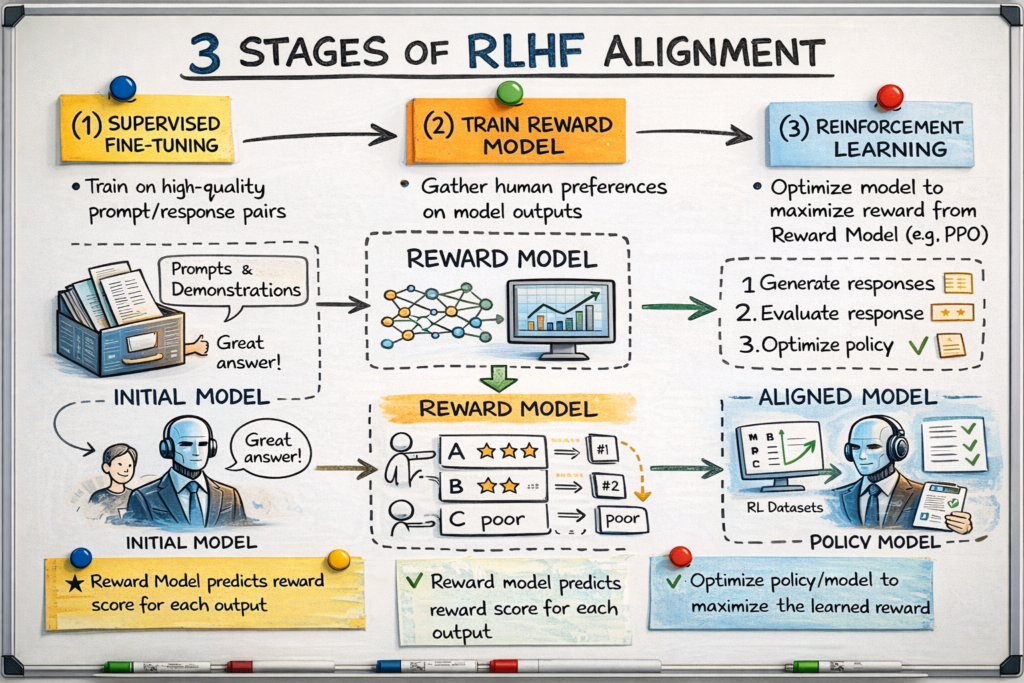

RLHF is an advanced fine-tuning strategy that further aligns the model’s behavior with what humans want by using a reinforcement learning signal derived from human feedback[52][53]. Essentially, instead of just showing the model the “right” answers (as in SFT), we interactively teach it which outputs are better through a reward mechanism. The process can be broken down into three major steps, iterating on the idea introduced in SFT:

- Collect human preference data & train a Reward Model (RM): First, humans are asked not to write answers, but to rank model-generated answers. We take the SFT model (or even the base model initially) and have it produce multiple responses to a variety of prompts. Human evaluators then look at, say, 2 or 4 responses to the same prompt and rank them from best to worst[54][55]. These ranked comparisons are collected in a dataset. Using this data, we train a separate neural network called a reward model that takes a prompt and an output and predicts a score for how preferable that output is, essentially trying to imitate the human rankings[54][56]. The idea is that the reward model learns the nuances of human preferences – it becomes a stand-in for a human evaluator. For example, if humans consistently rank responses that are more factual and polite higher, the reward model will learn to give higher scores to outputs that have those properties. OpenAI’s process for ChatGPT did exactly this, yielding a reward model after collecting tens of thousands of ranking examples[54][57]. Notably, creating the preference dataset is far more scalable than writing answers from scratch – ranking 5 outputs is quicker than writing 1 good output – so you can gather a larger dataset (OpenAI did this for ~30k prompts, an order of magnitude more than the initial SFT data)[54][58].

- Optimize the policy (the model) using RL to maximize the reward: Now we take the current model (e.g., the SFT model) and fine-tune it further with reinforcement learning. In reinforcement learning terms, the model is the “agent” that, given a prompt (“state”), produces a response (“action”), and then receives a reward score from the reward model (the “environment”). We use an algorithm (most famously Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)) to adjust the model’s weights to increase the reward it gets[59][60]. PPO is preferred because it’s relatively stable for fine-tuning large models – it avoids making too large of an update at once which could destabilize the policy[61]. Concretely, the model generates an output, the reward model scores it, and the PPO objective tweaks the model to slightly prefer outputs that would score higher next time[59][62]. Over many iterations, the model learns to produce responses that align better with human preferences as captured by the reward model. This could mean it becomes more factual, more helpful, less rude or less likely to produce forbidden content, depending on what the humans rewarded. The output of this step is often called the policy model (or just the RLHF-tuned model). In the case of ChatGPT, after this step, the model was significantly more aligned than after SFT alone[44][63].

- Iterate: In practice, steps 1 and 2 might be repeated – you can collect more human rankings on the newly improved model’s outputs to further refine the reward model, then do another round of policy optimization, and so on[64][65]. This iterative refinement can inch the model closer to ideal behavior. However, each round has costs and diminishing returns, so often only one or two rounds are done in large-scale training.

Figure: The three stages of RLHF alignment – (1) Supervised fine-tuning to produce a base aligned model, (2) training a reward model from human preference rankings, and (3) reinforcement learning (e.g. PPO) to adjust the policy/model to maximize the learned reward[66][63]. This process was used to train OpenAI’s InstructGPT and ChatGPT models, yielding significantly more helpful and truthful outputs than a pre-trained model alone.

The outcome of RLHF is a model that better reflects human-defined ideal behavior. For instance, compared to its pre-trained ancestor, ChatGPT (which underwent SFT+RLHF) is much more likely to refuse requests for disallowed content, to answer a question directly instead of dodging, and to say “I don’t know” rather than hallucinate wildly – because those behaviors were rewarded by humans during training[67][68]. It’s a powerful technique because it directly optimizes what we actually care about (human satisfaction with the answer) rather than a proxy like likelihood of text.

Key challenges in RLHF: While effective, RLHF is not without challenges and shortcomings. One issue is that the reward model is an imperfect proxy – it might have biases or blind spots based on the training data. If not carefully done, the model can learn to “game” the reward model (finding tricks to get a high score that don’t truly align with human intent, known as reward hacking). OpenAI mitigated this with the PPO KL-penalty technique, which keeps the new model’s answers from straying too far from the original distribution (to avoid extreme weird outputs)[69]. Another challenge is the quality of human feedback: if the labelers are not well-trained or if guidelines are flawed, the model will learn those flawed preferences[70]. For example, if the humans overly penalize any form of disagreement, the model might become excessively eager to agree or too cautious in answering.

There’s also the matter of scalability and cost. RLHF requires a lot of human-in-the-loop work – though ranking is easier than writing answers, you still need many people to provide feedback, plus the overhead of training an extra model (the reward model) and performing reinforcement learning which can be finicky. Companies like OpenAI have invested heavily in this, and now there are even third-party providers of RLHF-as-a-service to help others fine-tune models with human feedback[71][63]. But it remains a resource-intensive process.

Lastly, even with RLHF, models can still make mistakes or exhibit biases – they are more aligned, not fully aligned with all human values. It’s an active research area to explore improvements or alternatives (such as Constitutional AI by Anthropic, which uses AI feedback to some extent, or training on diverse preference data to reduce bias). Despite these challenges, RLHF has so far proven to be a key ingredient in turning powerful LLMs into useful conversational agents. As one source notes, ChatGPT was the first major deployment of an RLHF-aligned model, and it dramatically improved the model’s helpfulness and safety with only minimal loss in other capabilities[44][51].

Conclusion

Creating a large language model is a bit like raising a prodigy student: you first give them an encyclopedic education through self-study (pre-training), then mentor and coach them to behave and apply that knowledge usefully (fine-tuning and feedback). Each stage of this process – from collecting a corpus, to designing the neural network, to the months-long training, and finally alignment tuning – is critical and comes with its own technical challenges. Modern LLM development has been enabled by massive data availability, the Transformer architecture, and huge computing scale, but it’s the addition of alignment techniques like SFT and RLHF that turn a clever-but-unruly model into something that can reliably assist humans[68][52].

For professionals in AI, data engineering, or product management, understanding this pipeline is important. It highlights why developing an LLM from scratch is resource-intensive and typically limited to a few AI labs – yet it also shows where one can intervene to improve a model. For instance, data quality will directly affect model behavior, architecture and scaling decisions determine the ceiling of model capability, and alignment efforts address the gap between raw capability and useful behavior. Each phase also presents active research questions: How can we collect better and more diverse data? What architectures might surpass Transformers or make training more efficient? How can we align models with human values without needing so much human input?

In summary, building an LLM is a multidisciplinary marathon involving big data, clever algorithms, and human oversight. The result, when done well, is a model that understands and generates language with remarkable proficiency, and does so in a way that is helpful and safe for users. By breaking the process into these stages – pre-training (foundation) and post-training (alignment) – teams can tackle the immense complexity step by step, continually refining the “brain” of the model and then teaching it to be a good conversational citizen. The journey from a raw text-predictor to an aligned assistant encapsulates the cutting edge of AI today, merging unsupervised learning with human feedback to create technology that better serves human goals.

Sources: The description above synthesizes findings from recent literature and industry reports on LLM development. For example, data sourcing practices and the importance of diverse corpora are discussed in W&B’s LLM training whitepaper[1]. Details on model architecture and scaling are informed by both that whitepaper and analyses of models like GPT-3 (which had 175B parameters and required an estimated $4.6M to train)[34][27]. Training stability and techniques are also documented in practical guides[30][40]. The two-stage alignment process (SFT + RLHF) and its implementation in InstructGPT/ChatGPT are described by OpenAI and summarized in various sources[72][66], which explain how human demonstrations and feedback are used to significantly improve alignment[48][54]. These references (and others cited in-line above) provide a deeper dive into each aspect for those interested in the technical nuances of building LLMs.

[1] [3] [4] [5] [6] [8] [11] [25] [28] [29] [30] [37] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [51] [52] [53] [63] [66] [71] Current best practices for training LLMs from scratch – Weights & Biases

https://wandb.ai/site/articles/training-llms

[2] [7] [26] [27] [34] [35] OpenAI’s GPT-3 Language Model: A Technical Overview

https://lambda.ai/blog/demystifying-gpt-3

[9] [10] [12] [14] [15] Data Collection and Preprocessing for LLMs [Updated]

https://www.labellerr.com/blog/data-collection-and-preprocessing-for-large-language-models

[13] [16] [17] [49] RLHF: Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

https://huyenchip.com/2023/05/02/rlhf.html

[18] [19] [22] [23] [24] How tokenizers work in AI models: A beginner-friendly guide

https://nebius.com/blog/posts/how-tokenizers-work-in-ai-models

[20] Understanding Tokenization. BPE, WordPiece, and SentencePiece …

[21] What are the types of tokenizers? – AI Stack Exchange

https://ai.stackexchange.com/questions/47214/what-are-the-types-of-tokenizers

[31] [32] [33] [45] [46] [47] [48] [50] [54] [55] [56] [57] [58] [59] [60] [61] [62] [64] [65] [67] [68] [69] [70] [72] How ChatGPT actually works

https://www.assemblyai.com/blog/how-chatgpt-actually-works

[36] What is accelerated years in describing the amount of the training …

[38] What is the cost of training large language models? – CUDO Compute

https://www.cudocompute.com/blog/what-is-the-cost-of-training-large-language-models

[39] Mosaic LLMs: GPT-3 quality for <$500 k – Databricks

https://www.databricks.com/blog/gpt-3-quality-for-500k