Introduction

Stablecoins – digital tokens pegged to fiat currencies like the U.S. dollar – have rapidly become integral to the crypto and fintech landscape. From facilitating crypto trades to enabling fast cross-border payments, stablecoins fill a critical need for price-stable digital value. However, not all stablecoins are built the same. The companies issuing them, their business models, and their strategies can differ widely, leading to divergent outcomes in adoption, profitability, and regulatory treatment. This deep-dive provides a comprehensive overview of who issues stablecoins, how they make money, emerging trends in the sector, and a comparison of regulatory approaches in the EU vs the USA.

The Issuers: Who Is Minting Stablecoins?

Stablecoin issuers today range from crypto-native firms to banks and even central banks. Key categories of issuers include:

- Specialized Crypto-Native Firms: These are fintech companies born in the crypto industry whose core business is stablecoin issuance and reserve management. Tether and Circle are prime examples, together accounting for roughly 90% of all stablecoin market capitalization reuters.com. These firms issue popular coins like USDT (Tether) and USDC (Circle) and generate revenue primarily from investing the fiat reserves backing the coins. Paxos is another crypto-native issuer, known for issuing its own USDP stablecoin and powering others’ stablecoins (like Binance’s BUSD in the past and PayPal’s coin today). Such firms dominate the market currently by specializing in stablecoin operations and maintaining large reserve portfolios.

- Payment Companies & Fintech Platforms: Major payment processors and fintech apps have begun issuing stablecoins as an extension of their services. For example, PayPal launched PayPal USD (PYUSD) in 2023, issued through Paxos Trust Company paxos.com. For payment platforms, a stablecoin can enhance their ecosystem by enabling instant user-to-user transfers, blockchain payments, and new financial products. The goal is often to drive user engagement, lower payment costs, and keep customers within their platform’s network. Other payment firms like Stripe and Visa are integrating stablecoin capabilities (though not issuing their own coins) to facilitate faster transactions dtcc.com dtcc.com. By issuing or using stablecoins, payment companies aim to leverage blockchain’s speed and 24/7 availability while retaining control over the user experience.

- Banks and Financial Institutions: From global banks to regional banks, many traditional institutions are exploring or launching their own version of stable digital money. For instance, JPMorgan’s JPM Coin is a tokenized bank deposit used internally for corporate clients, processing over $1 billion in daily volume for cross-border and interbank settlement dtcc.com. Some banks are experimenting with “tokenized deposits” – essentially digital dollar tokens recorded on bank-ledgers or private blockchains – which function like stablecoins for settlement purposes. A consortium of U.S. banks had even formed the USDF network to launch a bank-backed stablecoin (though progress has been slow). Central banks also encourage this convergence: many regulators see bank-issued tokens as a safer model for stablecoins within the banking perimeter. In short, banks are entering the space to modernize payment rails and defend against fintech competition, blurring the line between traditional deposits and stablecoins on blockchain.

- Big Tech Initiatives: Large technology companies have eyed stablecoins as well, viewing them as a way to embed payments and financial services into their platforms. The most prominent example was Meta’s (Facebook’s) proposed stablecoin Libra, later rebranded to Diem. Meta assembled a consortium to launch Libra, envisioning a global stablecoin for payments within Facebook’s apps. However, the Diem project was abandoned in early 2022 amid intense regulatory and political pushback cointelegraph.com. Regulators were concerned about a tech giant potentially controlling a global currency, which led to the project’s assets being sold off. This high-profile failure illustrates the challenges Big Tech faces entering finance. Nonetheless, tech platforms continue to explore digital currencies on a smaller scale – for example, Telegram launched a stablecoin for its users in 2023, and there are reports of Meta exploring stablecoin payments again under a more compliant approach. Tech firms see stablecoins as tools to lock users into their ecosystems (for purchases, gaming, remittances, etc.), but they must overcome regulatory hurdles and public trust issues to succeed.

- Central Banks (CBDCs): While not typically labeled “stablecoins,” central bank digital currencies share a key principle: they are fiat-backed digital tokens redeemable 1:1 in official currency. Dozens of central banks are researching or piloting CBDCs – from China’s digital yuan to Europe’s proposed digital euro. The distinction from private stablecoins is that CBDCs are issued and fully guaranteed by central banks, not private companies. However, in practical usage they compete in the same arena: providing a digital form of money with stable value. CBDCs can be seen as public-sector counterparts to stablecoins, addressing similar use cases (payments, settlement) but with government backing. Some nations (like Nigeria and The Bahamas) have already rolled out retail CBDCs. Others, like the U.S., are undecided – partly because private USD stablecoins are already filling the demand for digital dollars. In summary, central banks are cautious of stablecoins’ rapid growth and are responding with their own digital cash initiatives. The coexistence or competition between private stablecoins and CBDCs will be an evolving dynamic in coming years.

Business Models of Stablecoin Issuance

Despite similar outward products (a token pegged to fiat), stablecoin issuers can have very different business models underpinning how the coins are issued and who profits from them. Two primary models have emerged:

- Direct Issuance Model: In this model, the company that issues the stablecoin manages the entire process directly – minting new coins, handling redemptions, and managing the reserve assets. Customers typically deposit fiat currency with the issuer (or its banking partners) and receive newly minted stablecoins in return; when they redeem, the issuer returns fiat and burns the corresponding tokens. Direct issuers maintain full control of the reserves and therefore keep the revenue generated from those reserves (e.g. interest on bank deposits or government bonds). Tether (issuer of USDT) and Circle (issuer of USDC) exemplify this model. They invest their stablecoin reserves in highly liquid, low-risk assets like U.S. Treasuries, repos, and cash equivalents, earning significant interest income cointelegraph.com cointelegraph.com. This interest income has become enormous with higher interest rates – for example, Tether earned an estimated $13 billion in net profits during 2024 alone from its reserves and related activities dtcc.com. Tether’s revenue model is straightforward: it retains all interest and other income from managing ~$80+ billion in assets, yielding very high profit margins. Circle’s USDC operates similarly but with a twist: to drive adoption, Circle shares a large portion of its reserve interest revenue with distribution partners (like Coinbase, which co-founded USDC). In fact, Circle’s filings revealed that over 60% of its $1.68 billion reserve interest revenue in 2024 was paid out to partners (Coinbase alone received about $908 million) medium.com. This leaves Circle with a thinner profit margin (~9% in 2024 media-publications.bcg.com) compared to Tether’s hefty profits, but Circle’s strategy is to incentivize wider usage of USDC by effectively rewarding the platforms that bring in users media-publications.bcg.com. In a direct issuance model, the core revenue engine is the interest from reserves (which scales with the float of stablecoins in circulation), and the key decision is whether to keep or share that revenue. Tether’s strategy is to keep it (maximizing profit), whereas Circle’s strategy is to share much of it in exchange for growth and integration into more platforms.

- White-Label or Partnered Issuance Model: In this model, the stablecoin is issued by a dedicated infrastructure provider on behalf of another brand or partner. The issuing firm handles the technical issuance, regulatory compliance, and reserve management in the background, while the partner company owns the customer relationships and promotes the stablecoin under its own brand. Paxos Trust Company has pioneered this white-label approach in the USD stablecoin space. For example, PayPal’s PYUSD stablecoin is issued by Paxos but carries the PayPal brand and is integrated into PayPal’s user app paxos.com. Similarly, in late 2024 Paxos launched the Global Dollar (USDG) in partnership with a consortium including Robinhood, Kraken, and others – Paxos mints the token, but it is governed by a committee of the partner firms and aimed at their users reuters.com. In white-label arrangements, the economics are often flipped compared to direct issuance: the partner (brand) keeps most of the reserve interest revenue, while the issuer (infrastructure provider) earns fees for managing the stablecoin program. This was seen with the now-defunct Binance USD (BUSD) where Binance reaped the benefits while Paxos took a small cut, and it’s evident in Paxos’ recent partnerships. Paxos’ CEO described the Global Dollar Network’s model, noting it will “return virtually all [reserve] rewards to participants” (i.e. the partner firms) to incentivize adoption reuters.com. The issuer thus makes money through fixed fees or management fees rather than net interest spread. Both direct and white-label models rely on the same underlying mechanics of 1:1 backing and secure reserves; they primarily differ in who interfaces with end-users and who captures the bulk of the interest income. Direct issuers maintain control (and profits) centrally, whereas white-label issuers operate more as B2B service providers, enabling others to offer a stablecoin without building the infrastructure from scratch.

Example – Direct vs White-Label: Tether’s USDT and Circle’s USDC are direct-issued: these companies directly serve exchanges, traders, and institutions wanting stablecoins, and they profit from the assets held in reserve (Tether retains all interest; Circle splits it as noted). In contrast, Paxos’ role in PayPal USD and USDG is a white-label issuer: PayPal or the USDG consortium handle distribution and user acquisition, while Paxos trusts earns a fee for ensuring the coins are fully reserved and redeemable. The white-label model appeals to companies that have a user base or platform (exchanges, fintech apps) and want a custom stablecoin to enhance their product – they can essentially outsource the technical and regulatory heavy lifting to an expert issuer. This is why distribution partnerships have become crucial: an issuer like Circle or Paxos may sacrifice some economics to get their stablecoin widely distributed via popular platforms (exchanges like Coinbase or fintech apps like PayPal), since mere issuance alone doesn’t guarantee people will use the coin. As we’ll see, this focus on distribution is a growing trend in the stablecoin industry.

Emerging Trends and Strategies in Stablecoins

Stablecoins sit at the intersection of technology, finance, and regulation, and the sector is evolving quickly. Several key trends are shaping how stablecoins are issued and used:

- Distribution is King – Partnerships Drive Adoption: A clear lesson in recent years is that a stablecoin’s success depends on being widely usable and available where users want it. Issuers have adapted by forging partnerships to distribute their coins. Circle’s willingness to share revenues with Coinbase (and previously Binance) is one example of seeding adoption media-publications.bcg.com. Paxos paying out most reserve income to partners like PayPal or the USDG consortium is another reuters.com. These deals reflect the fact that issuance alone is not enough – stablecoins need integration into exchanges, wallets, and payment apps to gain users. Coinbase’s marketing of USDC and PayPal’s integration of PYUSD massively expand the reach of those coins, which ultimately benefits the issuer too (via higher volumes and credibility). This trend suggests stablecoin firms are increasingly operating more like payment companies, focusing on network growth and transaction volume rather than just float size. In essence, stablecoin issuers are willing to give partners a slice of the pie in order to make the overall pie much larger.

- Tokenization as the Next Growth Driver: While stablecoins today are heavily used in cryptocurrency trading and simple payments, their biggest impact may be in the tokenization of traditional assets. Financial markets are starting to tokenize assets like securities, bonds, and real estate – representing them as blockchain tokens – and stablecoins are the natural medium of exchange and settlement in these tokenized markets. Already, stablecoins are becoming “foundational pillars of global liquidity” in blockchain-based capital markets dtcc.com. Industry analyses point out that stablecoins are playing a key role in real-world asset (RWA) tokenization, such as tokenized money market funds, government bonds, and other instruments dtcc.com. The vision is that in the near future, a tokenized stock trade or a digital bond issuance could settle instantly in stablecoin (a digital dollar) instead of through the slow banking system. This could unlock 24/7 trading and near-instant settlement for a wide range of assets. For instance, mortgage loans or real estate shares could be tokenized and exchanged for stablecoins, bringing liquidity to historically illiquid markets. Major institutions are investing in this future: e.g., Citibank has developed tokenization services enabling other banks to issue stablecoins for settlement dtcc.com, and JPMorgan’s blockchain network has used JPM Coin to settle tokenized asset trades in real time media-publications.bcg.com. While still early, these developments indicate that stablecoins might graduate from a niche in crypto trading to a central role in mainstream financial transactions. As one report noted, stablecoins are bridging traditional finance (TradFi) and decentralized finance, potentially becoming the de facto settlement layer for a tokenized economy dtcc.com.

- From Interest Income to Transaction Fees: The current profitability of stablecoins is driven by interest on reserves – essentially a byproduct of holding users’ money. But this may not last forever. Interest rates could fall, and competition (or regulation capping reserve assets) could compress this income. The next phase for stablecoin business models may shift towards transaction-based revenues and ancillary services. We already see hints of this: Tether, for example, reportedly earns sizable revenue from fees on transfers and redemptions, especially via its partnerships with exchanges cointelegraph.com. In early 2025, Tether was collecting over $122 million per week in fees across various blockchains, over $6.4 billion annualized cointelegraph.com – showing that transaction fees can be extremely lucrative at scale. Future revenue streams might include payment processing fees, wallet services, API access for merchants, and other utility fees associated with using stablecoins in commerce. In other words, stablecoin issuers could evolve to resemble payment networks (earning a small cut of each transaction) rather than pure asset managers. For example, if stablecoins become popular for remittances or retail payments, companies like PayPal or Circle might charge interchange-like fees. This would align stablecoin economics more with traditional payments, and less with the “float income” model that looks like a bank. Notably, Circle has been investing in payment and custody infrastructure (such as its cross-chain transfer protocol and merchant APIs) to enable more transactions in USDC, hinting at a strategy beyond just collecting interest. Overall, as the stablecoin sector matures and if interest margins narrow, expect a pivot towards monetizing usage – much like how credit card companies profit from card swipes rather than holding deposits.

- Convergence of Banks and Fintechs: The line between a “stablecoin” and a “bank deposit” is growing blurrier, especially under regulatory pressure. Banks are developing their own digital dollar tokens (often called deposit tokens), while fintech stablecoin issuers are being pushed to operate more like banks. Regulatory frameworks in various jurisdictions are encouraging this convergence. In the EU, for instance, the new MiCA regulation limits stablecoin issuance to licensed banks or electronic money institutions morganlewis.com, effectively pulling stablecoins into the traditional regulated banking perimeter. In the U.S., recently passed legislation (the **“GENIUS Act” of 2025) will allow only regulated entities – like bank subsidiaries or specially licensed non-banks – to issue payment stablecoins, with oversight by federal banking regulators arnoldporter.com arnoldporter.com. The implication is that standalone crypto firms will either become more bank-like (obtaining licenses, submitting to bank-like supervision) or partner with banks to continue issuing stablecoins. Conversely, banks see opportunity in stablecoins and are leveraging their strengths (trust, compliance, large customer bases) to enter the market. We already have major banks like JPMorgan with their own coins, and others like Societe Generale launching stablecoins (e.g. a Euro stablecoin) dtcc.com. Small banks have also tested networks to issue interoperable stablecoins backed by deposits. Over time, we may end up with a spectrum of offerings that are functionally similar: a tokenized bank deposit and a stablecoin held under a trust framework might both give users a digital dollar, instantly transferable on a blockchain. Regulators appear to favor a model where stablecoins carry similar safeguards to bank deposits (asset backing, capital, audit requirements, etc.), making them safer but also reducing the distinction between a “crypto-dollar” and an ordinary dollar in the bank. This convergence is also evident in terminology – some suggest using the term “digital deposit” or “payment stablecoin” to emphasize that these tokens should be as reliable as money in a bank account. The convergence trend means increased collaboration between fintech issuers and traditional banks, and likely fewer unregulated issuers. It could also lead to interoperable networks where banks and non-banks transact with each other’s digital dollars seamlessly. In short, the stablecoin industry is losing its Wild West character and moving toward the embrace (and constraints) of the established financial system.

- Diverging Issuer Strategies: Even as the industry moves toward maturation, individual stablecoin issuers are pursuing different strategic paths:

- Tether focuses on dominance in crypto trading markets and maximal profit retention. It has resisted disclosing too much detail about reserves but has capitalized on high interest rates to generate unprecedented profits cointelegraph.com. Tether’s strategy bets on its first-mover advantage and sheer scale (it is by far the largest stablecoin) to maintain trust, even without heavy compliance or revenue-sharing partnerships.

- Circle is taking a more collaborative and compliance-forward route – partnering with major players (Coinbase, BlackRock, Visa, etc.), complying with regulations in multiple jurisdictions, and even launching euro-based stablecoins. Circle seems willing to trade short-term profits for long-term ubiquity of USDC, aiming to be the most widely accepted regulated stablecoin. Its upcoming public listing (via SPAC/IPO) and transparency efforts underscore this approach medium.com. Circle’s challenge is maintaining profitability if interest income falls; hence its push into new revenue streams and markets.

- Paxos is positioning itself as the behind-the-scenes infrastructure provider. After the BUSD episode, Paxos doubled down on being the regulated partner for others (like PayPal, brokers, and the USDG consortium). Paxos collects fees for its services and lets the partner brands shine. Its strategy banks on trust and tech prowess – if more companies or banks decide to issue a stablecoin, they might just use Paxos’ platform instead of reinventing the wheel. Paxos also runs other businesses (like securities settlement) that could synergize with its stablecoin capabilities.

- Other emerging players (like Circle’s competitors or new fintech startups) might differentiate on technology (e.g. faster blockchains, multi-chain support), on specific markets (some focus on Latin America or Asia with local currency stablecoins), or on compliance (advertising their fully audited reserves and regulatory approvals). We also see consortium models like USDF (banks consortium) or USDG (crypto firms consortium) trying more decentralized governance approaches to capture network effects.

- Tether focuses on dominance in crypto trading markets and maximal profit retention. It has resisted disclosing too much detail about reserves but has capitalized on high interest rates to generate unprecedented profits cointelegraph.com. Tether’s strategy bets on its first-mover advantage and sheer scale (it is by far the largest stablecoin) to maintain trust, even without heavy compliance or revenue-sharing partnerships.

Ultimately, the stablecoin sector is in flux – with high revenue up for grabs but also growing regulatory oversight and evolving use cases. Next, we examine how regulators on opposite sides of the Atlantic are addressing this fast-moving industry.

Regulation: EU vs. USA Approaches to Stablecoins

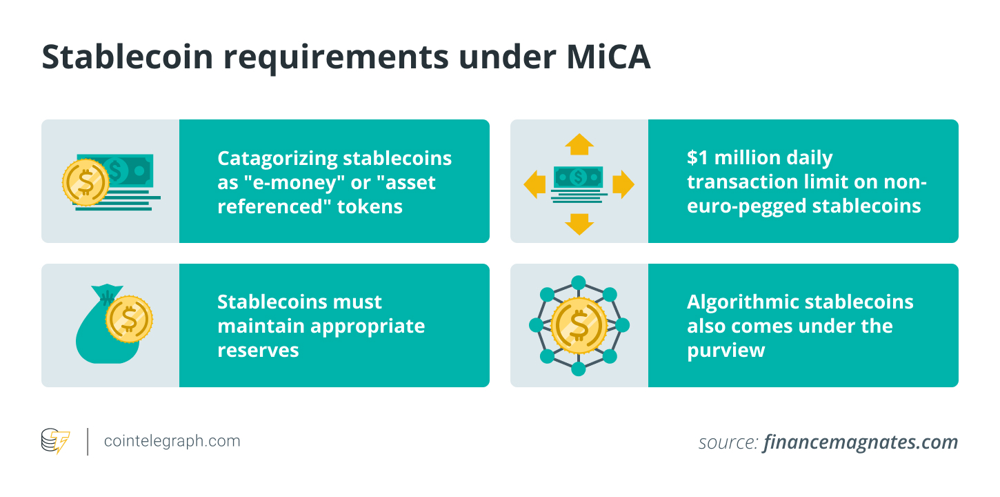

Key regulatory points from the EU’s MiCA framework on stablecoins (e-money tokens).

As stablecoins grew from fringe instruments to a global $125+ billion asset class, regulators have been racing to create guardrails. Notably, the European Union and the United States – two of the world’s largest financial jurisdictions – have taken distinct approaches to regulating stablecoins, reflecting different philosophies but a gradually converging goal of stability and innovation.

European Union – MiCA and Bank-Level Oversight

The EU has moved early and decisively with a comprehensive crypto-assets regulation known as MiCA (Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation). MiCA, which was passed in 2023, introduced a full regulatory regime for stablecoins (termed “e-money tokens” if fiat-pegged). As of June 2024, any fiat-backed stablecoin offered in the EU must comply with MiCA’s requirements morganlewis.com morganlewis.com. One cornerstone of MiCA is that issuers of stablecoins must be legal entities established in the EU and hold an appropriate license – effectively limiting issuance to banks or electronic money institutions in Europe morganlewis.com. This means a crypto company like Tether (not EU-based and not a bank) cannot legally market USDT to EU consumers unless it significantly changes its structure or partners with an EU licensed entity. MiCA also enforces strict reserve requirements: stablecoins must be 100% backed by reserves of specified high-quality assets (e.g. cash, central bank deposits, short-term treasuries), with regular audits and transparency reports. Issuers must guarantee par redemption rights (1:1 redemption at any time) to token holders morganlewis.com, and importantly, they are not allowed to pay interest to stablecoin holders (to prevent stablecoins from competing with bank deposits as interest-bearing accounts) morganlewis.com.

There are also operational rules – for example, MiCA imposes a €200 million daily transaction volume limit on large non-euro stablecoins used for payments in the EU (an attempt to limit widespread euro-substitution by something like a digital dollar)【31†source】. It also explicitly brings algorithmic stablecoins (not fully fiat-backed) under supervision, though purely algorithmic designs are essentially disallowed for consumer use under MiCA. In addition, the regulation addresses where reserves can be held: issuers like Paxos offering USD stablecoins in Europe are required to hold a portion of reserves in EU banks or investments coindesk.com coindesk.com, ensuring the EU has oversight and jurisdiction over the funds. The immediate impact of MiCA has been increased compliance among some stablecoins – Circle’s USDC, for instance, obtained licenses to be MiCA-compliant and is currently the largest regulated dollar stablecoin in Europecoindesk.com. On the other hand, stablecoins that didn’t meet the criteria faced market consequences: major EU exchanges delisted Tether (USDT) for European users in 2025 due to its non-compliance with MiCA’s transparency and licensing requirements cointelegraph.com.

In short, the EU is treating stablecoins much like traditional e-money: requiring licensure, capital, safekeeping of reserves, audits, and consumer protections. By pulling stablecoins into the regulatory perimeter early, the EU aims to foster innovation (by legitimizing stablecoins for mainstream use under clear rules) while mitigating risks like runs or misuse. It’s a top-down, harmonized approach across member states. Additionally, Europe’s stance is complemented by progress on a digital euro CBDC – some European officials prefer a public digital currency over reliance on private dollars. But until that materializes, MiCA ensures any stablecoin in the EU is as safe and accountable as possible under law.

United States – A Market-Driven Path Now Turning Regulatory Corner

The U.S., home to many stablecoin issuers and a huge user base, took a more laissez-faire approach initially, letting stablecoins grow under existing laws. Stablecoin issuers in the U.S. so far operated under a patchwork of state regulations: for example, Circle and Paxos are regulated as New York trust companies, subject to New York State’s stringent BitLicense and trust laws. Others, like Tether, operated offshore with limited U.S. oversight. There was no federal stablecoin law for years, and regulators used general consumer protection, anti-fraud, and securities laws to cover certain aspects (with debates on whether some stablecoins might be securities or commodities). This relative regulatory ambiguity allowed innovation but also led to concerns about systemic risk as stablecoin usage ballooned.

As of mid-2025, the U.S. is on the cusp of major regulatory changes for stablecoins. After extensive debates, Congress passed the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act (GENIUS Act) in July 2025, the first federal law specifically for stablecoins arnoldporter.com arnoldporter.com. The GENIUS Act creates a framework for “payment stablecoins” (stablecoins designed for payments and settlement) that parallels many principles seen in MiCA, but with an American twist. Key points include:

- Who can issue: Under the Act, only regulated entities can issue stablecoins – this includes subsidiaries of insured banks, new OCC-chartered entities specifically for stablecoins, or non-bank firms approved by state regulators under a federal oversight scheme arnoldporter.com. This opens the door for fintech firms to become licensed stablecoin issuers (with OCC approval) but also cements the role of banks in this space. Notably, the Act explicitly excludes tokenized bank deposits from its definition, leaving those to be handled as normal bank products arnoldporter.com. This signals that both banks and non-banks can participate, but under watchful eyes.

- Reserves and Disclosures: The law mandates full 1:1 reserve backing with safe assets (like short-term Treasuries, government money-market instruments, or cash) and regular audited disclosures of reserve composition and balancesarnoldporter.com arnoldporter.com. Issuers must publish monthly reserve reports, which are to be verified by independent auditors and certified by the CEO/CFO arnoldporter.com. These requirements aim to prevent any reserve mismanagement (as was feared with Tether historically) and to maintain public confidence via transparency.

- Redemption rights: Similar to the EU, U.S. rules will ensure that stablecoin holders can redeem their tokens for USD on demand at par, and likely will impose liquidity requirements so issuers can meet large redemptions. There will also be consumer protection standards and operational risk requirements spelled out by regulators.

- Federal vs State supervision: The GENIUS Act balances federal oversight with state regimes. A stablecoin issuer can be a state-authorized entity (like a state trust company) but would still have to meet federal minimum standards and likely register with a federal authority. Meanwhile, bank-affiliated issuers fall under their existing bank regulators. The Act gives primary regulatory responsibility to the Federal Reserve and OCC for ensuring compliance of non-bank issuers arnoldporter.com arnoldporter.com. This involvement of the Fed (which has been vocal about stablecoin risks) means oversight will be analogous to banking, even for fintech issuers.

- No interest to coin holders: Similar to MiCA, the U.S. legislation is expected to forbid paying interest to stablecoin users, to keep a line between stablecoins and bank accounts (this was a feature in earlier draft bills and aligns with global regulatory consensus morganlewis.com). Indeed, many current stablecoin terms of service already prohibit interest to users, with the issuer keeping the interest as revenue.

Up until this law, U.S. regulators addressed stablecoins through enforcement and guidance. For example, the NYDFS (New York Department of Financial Services) had issued guidance on reserve requirements for the stablecoins it oversaw, and it took action in 2023 against Paxos to halt issuing Binance’s BUSD over regulatory concerns bankingdive.com. The Federal Reserve had also signaled that stablecoin issuers should ideally be banks or subject to bank-like oversight, citing concerns about run risk and payment system stability coindesk.com. Now with the GENIUS Act, the U.S. is moving from an ad-hoc approach to a formal regulatory regime that in many ways mirrors the spirit of MiCA – protect consumers, ensure 1:1 backing, and integrate stablecoins into the traditional financial oversight framework.

One notable difference in the U.S. approach is the allowance for non-bank companies to become licensed stablecoin issuers (under OCC charter or state oversight) arnoldporter.com. This could enable current crypto-native firms like Circle or even big tech companies to issue stablecoins legally, without acquiring a full bank charter, so long as they comply with reserve and risk rules. The EU, by contrast, generally requires a banking or e-money license (which are harder to get for a startup). The U.S. approach is a bit more flexible in who can issue, reflecting a more market-driven stance, whereas the EU’s approach is more conservative (favoring established financial institutions). Another difference is the extraterritorial scope: MiCA seeks to regulate any stablecoin touching EU users morganlewis.com, whereas U.S. law will apply primarily to issuers operating in the U.S. (though overseas issuers like Tether could be indirectly forced to comply if they want access to U.S. markets or banking).

Common Ground: Despite different regulatory philosophies, the end state in both regions looks similar – stablecoins treated akin to a form of digital money that must be safe, fully backed, and run by accountable, regulated entities morganlewis.com. Both jurisdictions emphasize consumer protection and financial stability: ensuring that a stablecoin doesn’t collapse and cause wider damage, and that users don’t lose funds or fall victim to fraud. Both are also reacting to high-profile incidents (like Terra’s algorithmic stablecoin collapse in 2022) by clamping down on unbacked or risky stablecoin structures. Looking ahead, as global standards (e.g. from the Financial Stability Board) solidify, we can expect further alignment internationally – including in the UK, which is crafting its own rules, and in Asia where places like Hong Kong and Singapore are also instituting stablecoin regulations morganlewis.com morganlewis.com.

Conclusion

Stablecoins have evolved from an experiment on crypto exchanges to a critical component of modern digital finance. We now see a spectrum of issuance models – from crypto-native firms operating at tech speed, to fintech giants leveraging stablecoins for payments, to banks and even central banks issuing their own digital tokens. Each type of issuer brings different strengths: agility and innovation from fintechs, trust and scale from banks, user-centric design from tech platforms, and public mandate from central banks. Their business models, whether direct or white-labeled, determine how value is captured and who bears responsibility for the coins in circulation. Recent trends indicate that simply issuing a stablecoin is not enough; success lies in building networks, integrating into real-world uses (from DeFi to trading to settlement of everyday transactions), and adapting revenue models as the market matures.

Crucially, the rapid rise of stablecoins has prompted policymakers to ensure these digital dollars (and euros, etc.) operate safely. The EU’s MiCA and the U.S.’s upcoming stablecoin framework both aim to bring stablecoins into the regulatory fold, reducing the Wild West element and encouraging their use in a sound manner. This means the era of “regulatory arbitrage” for major fiat-backed stablecoins is likely ending – in the future, users may choose between a bank-issued digital euro, a regulated private euro token, or a digital dollar from a licensed U.S. fintech, all of which are transparent and fully reserved by law. The convergence of stablecoins with traditional finance is well under waydtcc.comarnoldporter.com, and it opens opportunities for broader adoption (e.g. mainstream payment apps or capital markets using stablecoins) as well as competition between incumbents and disruptors.

For crypto professionals, regulators, and fintech stakeholders, understanding these nuances is vital. Stablecoins are not monolithic – an asset like USDT differs in governance, risk, and strategy from one like USDC or a bank’s tokenized deposit. As the industry progresses, we will likely see continued innovation (e.g. multi-currency stablecoins, new technical standards), but within a framework of greater accountability. Whether one views stablecoins as a bridge to a more decentralized future or simply an upgrade to our payment plumbing, there is no doubt they are here to stay. With diverse players issuing them and authorities establishing rules of the road, stablecoins are poised to become an embedded feature of both the crypto economy and traditional financial systems dtcc.com – effectively bringing the stability of fiat currency into the digital, programmable realm.

Sources: Stablecoin industry analyses and news reports

regulatory frameworks (EU MiCA, US legislation) morganlewis.com arnoldporter.com, and press releases and statements from key market participants paxos.com cointelegraph.com. All cited materials provide further detail on specific points discussed.